Atomic India

How Hindu Nationalists learned to love the bomb

The Boston Globe,

By A.S. Hamrah

Oct 2002

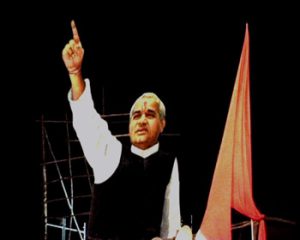

”BOMBAY IS A MINI-America,” says a holy man in ”War and Peace, ” Indian filmmaker Anand Patwardhan’s controversial documentary on the nuclear mania that has swept India since 1998. On the Buddha’s birthday that year, May 11, the government of Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee successfully exploded atomic bombs underneath the Pokaran desert, proudly showing Pakistan what-for until Pakistan exploded a few of its own. These ”Smiling Buddha” tests revived India’s dormant nuclear weapons program. Glorified by the ruling Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), celebrated in Indian popular culture, and decried by a grass-roots protest movement, a newly atomic India reminiscent of America in the decades after Hiroshima has emerged in a flash. ”Victory to Science” and ”Atoms for Peace” are its slogans, delivered Bollywood-style in music videos and on looming billboards. The holy man is in the pocket of the BJP; when he compares Bombay to America he does it to flatter. The current rulers of India look forward to a day when their country isn’t merely a mini-America but a superpower all its own. In the meantime A. B. Vajpayee is still known throughout the land as Atom Bomb Vajpayee.

”War and Peace” has won praise and prizes at film festivals around the world, including Bombay’s, but it is effectively banned in its home country. The censor board continues to demand cuts on a variety of trumped-up charges. ”They just don’t like it,” Patwardhan said at a late-September screening of the documentary at the Harvard Film Archive. It seems the BJP doesn’t want to be reminded of India’s Gandhian tradition of nonviolence and opposition to empire when they’re building an atomic empire of their own. In fact, archival footage re-creating Gandhi’s assassination is one of the scenes the Indian censors want excised. Although the Indian press has been supportive of Patwardhan, the government isn’t budging. Patwardhan senses a whiff of Joe McCarthy and the American 1950s in the air, and not just in India. Last February, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City delayed and relocated a screening of two of Patwardhan’s earlier films after receiving ”threats of violence” from activists denouncing them as ”anti-Hindu.”

In ”War and Peace, ” an Indian anti-nuclear journalist describes the arms race and its opposition as a struggle for India’s soul. The BJP, he says, feels ”that there must be some sort of shortcut to India being great, and the version that they are seeking to impose is that of a belligerent and aggressive nationalism.” Patwardhan cuts to a billboard showing Indian soldiers posed a la Iwo Jima, planting their country’s flag alongside the words ”Smile India.”

The struggle for America’s soul waged in the early atomic era was won handily in our pop culture. Writers and intellectuals fought atomic terror with essays and petitions, but musicians and marketers reacted with a wry humor and a misplaced whimsy that has had a more lasting impact. Bebop musician Slim Gaillard’s 1945 song ”Atomic Cocktail” set the standard by which future uses of the adjective atomic would be measured. Once the word had been attached to booze, using it to ramp up the va-va-voominess of postwar romance wasn’t far behind. Hot-cha atomic womanhood reached its apotheosis in Wanda Jackson’s rockabilly hit ”Fujiyama Mama.” ”I’ve been to Hiroshima, Nagasaki too, the things I did to them, baby, I can do to you,” yelped Jackson, and the bond between sex and atomic devastation was sealed forever. The ultimate trivialization of the bomb came in a candy wrapper, with the mouth-scorching Atomic Fire Ball, created in 1954 and with us to this day. The Web site of the Ferrara Pan Candy Co. tells of a Manhattan Project writ small: ”The `Atomic Fire Ball’ gained worldwide recognition shortly after the product was introduced. The round, spicy, hard candy that was once a dream had become a success.” Just like the A-bomb.

After the successful launch of that product in July of 1945 at White Sands, N.M., physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer told a TV interviewer that lines spoken by the god Krishna in the ”Bhagavad Gita” had flashed in his mind: ”I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” In India in 1998, India’s nuclear fathers announced that the Buddha smiled and looked for a suitable cross-cultural response, too. They found it in American-style show biz. If Oppenheimer searched the sky and saw reflected in the mushroom clouds the sublime myths of an older culture, the fathers of India’s nuclear program, though they named the Agni missile for the Hindu god of fire, have adopted the not-so-sublime forms of a newer culture.

The arms race with Pakistan has inspired the entertainment-makers of Bollywood and beyond. As a banner at an arms trade show in ”War and Peace” reads, ”To witness this mega event, visibility is the key.” Folksy carnivals sponsored by political parties like the Parel Ganesh Festival laud Indian nuclear superiority with a cast of mannequins and colored lights. Baseball caps bearing the symbol of the atom and the slogan ”Nuclear India – Global Peace Power” are passed out. Cadbury’s 5 Star Energy Bar sponsors a musical called ”An Evening for Martyrs,” which features a Bombay-style Backstreet Boy surrounded by showgirls. Honda pays for a spectacle called ”The Fifty-Day War,” a combination of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and a Disneyland ride from the 1950s that ends when a Sergeant York-like hero from the Line of Control dividing Indian- and Pakistani-controlled Kashmir is handed a bouquet and waves.

Patwardhan’s film shows Indian science being heralded in a way guaranteed to remind American viewers of 1950s science-fiction films, and in Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, a Muslim nuclear scientist who recently assumed India’s largely ceremonial presidency, India seems to have produced a happier Dr. Strangelove. Along with images of deformed children born near nuclear power plants, ”War and Peace” presents Indian scientists as lab-coated evangelists for a better tomorrow through radiation. In the United States the all-knowing man of science has become a figure hooted at during screenings of old industrial films. Here, public relations professionals do the talking for big science, but in India the scientists are still heroes, feted and given a forum. They’re living embodiments, we’re told, of India’s new star power.

The atom bomb has come to India with another American tradition – the curbing of works that seek to expose its dangers. Patwardhan interviews several American historians about a Smithsonian exhibition planned and then retooled in 1995. Designed to feature the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped that bomb on Hiroshima, and to catalog atomic destruction in Japan, the exhibit was branded anti-American by veterans’ groups and dramatically altered after accusations of treason that echo the charges leveled in India at ”War and Peace. ” The museum show as realized was as one-sided as a Jerry Bruckheimer epic. Instead of close-ups of the keloid scars of the victims of Hiroshima, it gave the public helicopter shots of a city in ruins – the only photographs of the bombing used in the show.

That kind of political interference hasn’t only affected highfalutin presentations like exhibits at national museums and independent film documentaries. In 1950, the Sons of the Pioneers, the western musical group that gave Roy Rogers his start, recorded an ill-fated song called ”Old Man Atom.” It was penned by a newspaperman named Vern Partlow in 1945, soon after the explosions in Japan. It’s something like the Louvin Brothers’ ”Great Atomic Power,” but without references to the Rapture. After the shhh… boom of a bomb blast, ”Old Man Atom” slides into the haunting vocal harmonizing familiar from other Sons of the Pioneers tunes, but in this song the group sings about a different kind of prairie:

Hiroshima, Nagasaki, A lamogordo, Bikini…

Narrated by the atom itself in a basso talking blues, the song relates the story of the new atomic age. A cautionary tale, it explains how:

T he science boys from every clime,

They all pitched in overtime.

And before they knew it the thing was done

And they’d hitched up the power of the gol-durn sun

And put a harness on ol’ Sol,

Splittin’ atoms while the diplomats were splittin’ hairs.

Humankind faces a choice, ”Old Man Atom” concludes: Get together or disintegrate.

RCA Victor sensed a hit in what was really a novelty song. Before ”Old Man Atom” was released, other pop stars of the day, including Bing Crosby, lined up to record it. But when the song came out, organizations like the Joint Committee Against Communism began to protest. RCA Victor pulled the disc from distribution and replaced it with a Pioneers song called ”Where Are You.’ ‘ Heard in the context of Hiroshima, ”Where Are You” sounds more ominous than ”Old Man Atom.” (”Then the sun goes to rest/ In the arms of the West. / But my own arms caress/ Emptiness. / Where are you?”) It would’ve worked as well as Vera Lynn’s ”We’ll Meet Again” as the music at the end of ”Dr. Strangelove, ” when Slim Pickens rodeo-rides a missile to nuclear oblivion.

Today it seems strange that the premier singing cowboys of their day recorded an atomic song that was suppressed. After all, they also waxed sides with titles like ”America Forever” and ”What This Country Needs.” Yet there had always been a campfire-lit, closing-time-in-the-gardens-of-the-Old-West feel to their music, an apocalyptic melancholy that expresses itself through unearthly hoofbeats heard in the night, raging sunsets and abandoned towns. A song like ”Rollin’ Dust,” recorded a few months before ”Old Man Atom,” strikes the same note.

Oh, the years are long and many since

they rode down into town.

It’s now just weeds and wormy boards and

shacks all tumbled down.

Where once they stood up to the bar and pretty

girls discussed,

They now hear ghostly laughter through a veil of heavy dust –

Rollin’ dust.

If that song, recorded at the dawn of the atomic age, doesn’t evoke the nuclear tests in Nevada and New Mexico and the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with their dark clouds and houses blown to splinters, what tune from that era does?

Korla Pandit played an eerie organ for the Sons of the Pioneers on that and other tracks. A musical personality from the early days of television who claimed he was a native of New Delhi (though he was probably an African-American from Missouri), Pandit forms a coincidental link between the Pioneers’ ghost riders in the sky and what an anti-nuclear politician in ”War and Peace” calls ”the fully armed gods of India.” In Hindu belief, the deity Krishna was the adoptive son of the cowherd Nanda. The movement of cows from one place to the next has always been central to both US and Indian culture, and now India gets to play nuclear cowboy, too.

This cowboy lurks at the heart of ”War and Peace.” In one scene, at an Indo-American Society convention featuring pamphlets like ”Learn Personality Development the Indo-American Way,” the camera finds an unsmiling man in a pin-striped suit and black ten-gallon hat. Floating through the crowd silent and alone, he looks like a Bollywood George Raft cast in the role of a western badman. Maybe he has read the pamphlet. By the end of the movie it’s clear that the men in charge of India’s nuclear future have taken more than a glance at it.

This story ran on page D2 of the Boston Globe on 10/13/2002.

© Copyright 2002 Globe Newspaper Company.