‘The World Is Family’ Review: A Wistful Chronicle of Personal Politics Beginning in India’s Freedom Movement

Documentarian Anand Patwardhan employs home video footage and faded photographs to explore the country's trajectory through an intimate lens.

By Siddhant Adlakha

India’s premiere DIY documentarian Anand Patwardhan turns his lens homeward in “The World Is Family,” a personal chronicle of India’s freedom movement and its contemporary cultural milieu. Through interviews with his aging parents and their friends and family, the director transforms his collection of lo-fi footage and old, monochrome photographs into a patchwork of political memory, resulting in one of the most moving films this year.

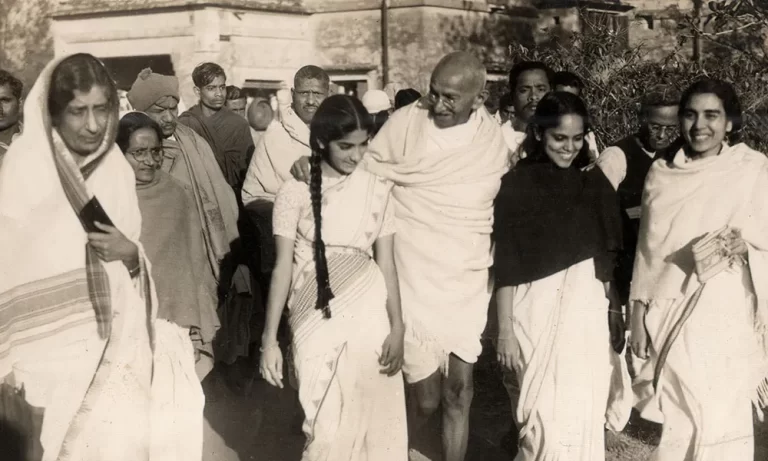

Patwardhan’s 1992 breakout “Ram ke Naam” (“In the Name of God”) was a prescient chronicle of India’s growing Hindu supremacist movement, while several of his other works, like “Jai Bhim Comrade” from 2011, shed light on the country’s caste hegemony. These perspectives and more inform his familial portrait too, which seeks to explore the intimate details of his parent’s youth under British rule, his uncles’ revolutionary activities alongside Mahatma Gandhi, and the ways in which the Gandhian dream of secular liberation has succeeded and failed in the years since India’s independence in 1947.

That year proves pivotal for Patwardhan’s narrative, since it also saw the Partition of India and Pakistan, as well as the subsequent mass migration of millions, including his family. Through interviews casually conducted in the mid-2000s — home videos that weren’t originally intended for cinematic use — the filmmaker creates a living archive of forgotten family ties in lieu of available documentation and images from the era. A visit to his mother’s ancestral, pre-Partition home (a rare opportunity for Indians and Pakistanis) reveals that it’s now a hospital, run by a kindly Pakistani doctor who’s eager for her to visit, but the red tape and militarism engulfing both countries complicates even small acts of friendship. Scant footage exists of Patwardhan’s uncles, the known revolutionaries Rau and Achyut, but hearing tales of their personal exploits from those who knew them makes them feel more real, more tactile — and it makes their absence felt.

Patwardhan paints a wider picture of Indian society by acknowledging the advantages of his upbringing, and how his “higher” caste ensured economic stability. The film’s narrative and even its original, Sanskrit-language title wrestle with these notions of privilege; “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” (or “the world is one family”) is a phrase found in ancient Hindu texts, and a concept in direct contradiction with the religion’s entrenched, caste-ist power structures — a collectivist notion Patwardhan attempts to embody through his filmmaking.

He unfurls India’s social stratification through subtle forms of drama, and through seemingly fleeting interactions — for instance, with Hindu and Muslim children, to gauge their perspectives on the country’s trajectory — during his journey across locations important to his family history. His uncles’ names are engraved on faded public plaques, but these impromptu interviews with India’s youth, conducted near places and monuments built to a history slowly being overwritten, are more revelatory than any direct or verbose indictment of modern systems.

For the most part, his lo-fi digital lens remains trained on his parents. His mother Nirmala’s sharp, acerbic wit makes for a humorous unraveling of the past, though the similarity between her high-pitched voice and that of her son’s yields frequent, albeit welcome confusion about which of them is actually speaking in some moments. The audience is invited into the most intimate of worlds, where loved ones speak in a unified voice.

Similarly, Patwardhan’s jolly father Balu speaks in slurred, subtitled speech, owing to a medical condition. This depiction tugs at the heartstrings, not only because it forces the audience to more closely read his expressions of love, longing and jest, but because Patwardhan instinctively understands every word he utters without the need of interpretation. The captions are only for the viewer’s benefit.

In this way, the proximity of the camera (and of the director’s disembodied voice) to Patwardhan’s family becomes a constant reminder of the deeply personal dynamics at play between interviewer and subject, even when the larger history of India’s freedom struggle is the topic at hand. This filmmaking approach lends aesthetic credence to the age-old refrain: “The personal is political.” However, the complexities of that notion are also thoughtfully broached. “The World is Family,” by way of objections raised by Nirmala, also questions Patwardhan’s intent, and the increasingly blurred line between his filmmaking as a personal album and as a pragmatic political record for all the world to see — a matter of cinematic ethics that yields increasingly discomforting personal portraits the more Patwardhan’s parents age and the more they discuss their impending deaths.

Through his personal study of his family, Patwardhan endears us to the entwined history of Nirmala, Balu, Rau, Achyut, Gandhi and India as a whole. And as he reaches several inevitable crossroads, from personal grief to dismay over the country’s divisive direction, “The World Is Family” becomes a deeply affecting, immensely powerful cinematic lamentation of lost stories and details, and a desperate act of personal and political preservation before time runs out.