Wind that shook the barley

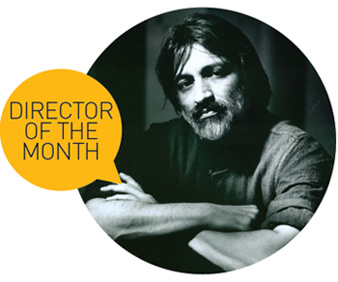

Meet the enfant terrible Anand Patwardhan who lets his camera do the talking

By Manjiri Indukar

A few days ago, I was narrating the story of Jai Bhim Comrade, Anand Patwardhan’s latest documentary film, to a friend. I told her

A few days ago, I was narrating the story of Jai Bhim Comrade, Anand Patwardhan’s latest documentary film, to a friend. I told her

that on July 11, 1997, 10 Dalits were shot dead during a police firing at Ramabai Colony near Ghatkoper in Mumbai. She interrupted to say, “Did you mean 100 or 10?” I quickly answered before continuing with the story. But, her question made me think; is 10 not a big enough number? Is there a magic digit that transforms an event to a tragedy? The more I thought, it became clearer that when it came to the margins, even thousands sometimes do not suffice. Perhaps it is this significance of a number and our collective conscience that pushed Anand Patwardhan to make Jai Bhim Comrade.

Simply, to introduce us to our own selves. Three days after the Mumbai encounter, poet-singer Vilas Ghogre, also a resident of the Ramabai Colony, took his life in protest. Ghogre, who had earlier worked with Patwardhan in another film of his believed that the “World was not a place worth living in anymore.” After Ghogre’s demise, Patwardhan made Jai Bhim Comrade. The documentary offers brutal, visceral moments of ‘complete truth’ in which Patwardhan successfully makes his audience flinch. Take an instance when a woman lectures Patwardhan on Brahmin pride. In another scene, a woman lets Patwardhan know that Dalits “should not be allowed to celebrate the anniversary of Bhim Rao Ambedkar in public places”.

Why? Because they are “very dirty people who create a lot of mess on the roads”. So “dirty” that one can tell them apart just by looking at them. While we still hear Patwardhan talking to the woman in mock seriousness and prodding her for more, our minds beg her to stop. And the camera too moves away from her. But India is a strange ambiguous land of contradictions; there are enough poignant moments where Patwardhan underlines this truth clearly.

When quizzed about his caste, a sweet-seller on the streets says: “Samosa, jalebi aur mithai yehi humari jaat hai (the sweetmeats that I sell, symbolises my caste).” The man laughs as the camera stays on him for a while before the scene dissolves and transforms into another. Though it is Patwardhan who asks his subjects difficult questions, he lets his camera do most of the ‘directorial’ talking. Though there are moments of inertia and friction in ways scenes are shot, indicating almost Patwardhan’s judgment of his subject, at the same time the director does give his viewers enough credit and breathing space to make up their minds.

When quizzed about his caste, a sweet-seller on the streets says: “Samosa, jalebi aur mithai yehi humari jaat hai (the sweetmeats that I sell, symbolises my caste).” The man laughs as the camera stays on him for a while before the scene dissolves and transforms into another. Though it is Patwardhan who asks his subjects difficult questions, he lets his camera do most of the ‘directorial’ talking. Though there are moments of inertia and friction in ways scenes are shot, indicating almost Patwardhan’s judgment of his subject, at the same time the director does give his viewers enough credit and breathing space to make up their minds.

t is no surprise that Patwardhan shoots and edits his films. While several documentary filmmakers treat their films as reality checks, Patwardhan sees them as art. So, a question begs to be asked, why not make films which are more ‘palatable’? “I am determined to break the documentary taboo.” He proudly lets me know that his films, too, are “in popular demand”. And he has seen thousands turn up for the screenings. “Why would you want me to give up the unparalleled power of documentaries in exchange for the forgettable entertainment that passes off as fiction?” A pertinent point. Possibly India does not have a big market for documentaries like the West, but things are certainly changing here. And Patwardhan has a lot to do with that change.

In 1991, a year before the Babri Masjid was demolished, Patwardhan made Ram Ke Naam (In the Name of God) as a warning to a foreseeable storm. The film was based on rising fundamentalism in India. The movie effectively captured on-the-rise militancy in a state that seemed ready to tear down edifices which did not cater to its version of ‘godly’. Having said that, Patwardhan’s films are not lopsided. They are more like open spaces with a scope to explore a topic. If on one hand he focused on the rising fundamentalism in Ram Ke Naam, on the other hand he looked at the secular forces. As is the fate of films that deal with “different” issues-In the Name of God did not pass the censorship scissors. As Patwardhan puts it, “The warning in the film was never heeded.” And Patwardhan often battles to get his films aired on Doordarshan (DD). “DD’s refusal to telecast my films has remained constant. Their stance is broken only when I win court cases against orders.”

In 1991, a year before the Babri Masjid was demolished, Patwardhan made Ram Ke Naam (In the Name of God) as a warning to a foreseeable storm. The film was based on rising fundamentalism in India. The movie effectively captured on-the-rise militancy in a state that seemed ready to tear down edifices which did not cater to its version of ‘godly’. Having said that, Patwardhan’s films are not lopsided. They are more like open spaces with a scope to explore a topic. If on one hand he focused on the rising fundamentalism in Ram Ke Naam, on the other hand he looked at the secular forces. As is the fate of films that deal with “different” issues-In the Name of God did not pass the censorship scissors. As Patwardhan puts it, “The warning in the film was never heeded.” And Patwardhan often battles to get his films aired on Doordarshan (DD). “DD’s refusal to telecast my films has remained constant. Their stance is broken only when I win court cases against orders.”

He is known to court controversies, so I had to ask, how does he choose his subjects? He tells me that he does not choose them. “Left to myself I prefer to relax rather than plunge into one film after the other,” says the man. Then how does he end up making such powerful films? “I make films on stories that need to be told honestly.” Patwardhan’s films are as haunting as the voices within us; the only difference is that he thinks them aloud instead of escaping. Though he has been making films for the past 30 years, he still determinedly funds them because he does not wish to be “influenced” by people who put in their capital. He hates being “pigeon-holed or labelled” as a Gandhian or Marxist. As a young scholarship student in America in the early 1970s, he was inspired by the likes of Martin Luther King and Cesar Chavez and went on to join the American Labour Movement on a wage of $5 per week for six months. A libertarian; Patwardhan is no more just an Indian documentary filmmaker. His films are popular among international critics and he is considered to be one of the foremost filmmakers of our time. His camera and him are travelling across the world asking questions that need to be asked and taking the controversial bull by its horns. When Patwardhan says something, he makes sure that everyone pays attention.