War and Peace (2002) monumental War Documentary more committed to peace than bloodshed (Review)

Graham Williamson 24/07/2015

War When Mark Cousins started his monthly column in Sight & Sound magazine in 2012, a large chunk of his inaugural piece was spent discussing the work of Anand Patwardhan. Patwardhan is one of those documentarians who the international film festival cognoscenti know and love, yet is almost completely unheard-of among the Western public. Why is this? Is it because his films are complex, elitist, difficult? No – watching Second Run’s world premiere DVD release of his 2002 film War and Peace, it struck me that it would be impossible to make a longer film about a serious issue that was more digestible, accessible and unpatronising than this.

In the DVD’s accompanying booklet (which, again, is as good as Second Run booklets always are), Cousins pops up again and ventures an explanation. Westerners, he suggests, see India as structureless, either a chaotic, bustling metropolis or a spiritual dreamworld. But Patwardhan’s films are explicitly about the structure of Indian society; the hidden agendas, cultural attitudes, backroom deals, bigotries and biases which shape the nation’s politics.

War and Peace is the result of nearly four years filming on the India-Pakistan border from 1998 to 2002, a turbulent period that saw both nations become nuclear powers, a brief but bloody war in Kashmir, and the inception of the War on Terror. It is also Patwardhan’s alternative history of Indian independence, starting with the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. Patwardhan finds a disturbing clip here of hands clasped together, apparently praying, that turn out to conceal the weapon that killed India’s liberator. He moves on from that national trauma to ask how a country born from the ethos of non-violent resistance could end up threatening its neighbour with an atomic bomb.

It is, for sure, a challenging and provocative film. In the extras, Patwardhan talks about the farcical, plainly biased attempts made to censor it in his home country, and there is also a clip from a Pakistani TV show where the merits and biases of the film are hotly debated. Yet what glues Patwardhan’s complex film together is, ultimately, compassion. The allegation made by one guest on the talk show that Patwardhan is prejudiced against Pakistan seems utterly ludicrous in the light of the scene where the director crosses the border and talks to Pakistani artists, schoolchildren and activists about their views on the bomb. The grace and tolerance of this scene seems to resurrect, all by itself, the silent-era dream that cinema’s international voice could be a driver of world peace.

At first, I thought Patwardhan had missed some context out which would explain why the two countries reacted in such different ways, but then I realised that was his point.

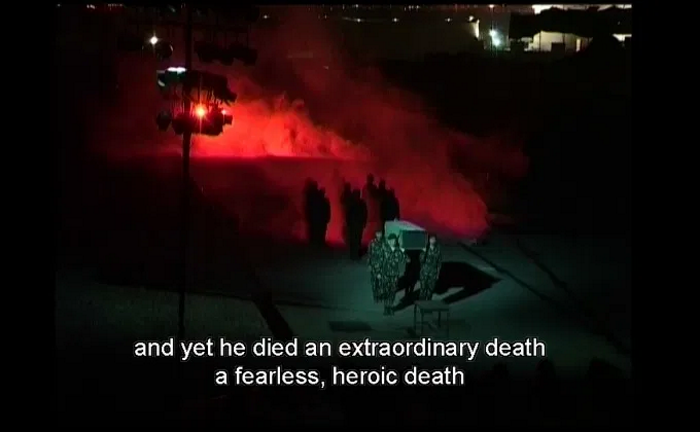

A common Achilles heel of documentaries made in the late 1990s and early 2000s is that the digital video technology dates so quickly. Although, as Patwardhan openly acknowledges, the film was made using small and cheap cameras to facilitate occasionally illicit shooting, the old-fashioned video of War and Peace actually adds to the film. Its lurid poster-paint colours are just the thing for capturing a hot Indian night, and it enables the film to switch back and forth from news clips to Patwardhan’s own footage seamlessly.

Yet you couldn’t confuse the two. Patwardhan’s shots are much more beautiful, particularly during a lyrical late sequence where he meets Indians who still hold to Gandhian principles. And although his film is never hectoring, his viewpoint comes across very clearly. He has a blanket opposition to nationalism, religious fundamentalism and prejudice, he finds the bomb an obscenity and he believes nuclear energy is just a fig-leaf to legitimise the production of nuclear weapons. The best contrast between the news’s viewpoint and his own comes in the aftermath of the 1999 Kargil war, where he cuts straight from the conflict to the aftermath; the Pakistani Prime Minister weakened and overthrown, the Indian Prime Minister valorised and celebrated. At first, I thought Patwardhan had missed some context out which would explain why the two countries reacted in such different ways, but then I realised that was his point. The war, in his eyes, was a tragedy without victors and losers. What happened afterwards was just about politics and public image.

In the second half of the film Patwardhan goes to Japan and America to see how they dealt with their nuclear legacies. It sounds like a bridge too far for an already jam-packed film, but instead it reinforces War and Peace’s status as a truly universal film about a local problem. The political circus surrounding the bomb in America is so unmistakably similar to the one whipped up by the Hindu nationalist BJP party – it eliminates any smugness Western viewers might feel upon seeing some of the more bizarre manifestations of jingoism Patwardhan uncovers in India and Pakistan.

Ultimately, for Patwardhan, all of this is worth documenting for the same reason; every bomb produced represents hundreds of schools not built, roads not maintained, schools not funded, children not fed. And what do they gain us? A chilling late interview clip shows a military scientist saying he now agrees with the anti-nuclear demonstrators: it would be madness to have a nuclear conflict in South-East Asia. Instead, he suggests, they should go to war with a country much further away, so they can try out their new long-range nuclear warheads. At this point, Padwardhan’s tolerance and humanity is evidenced by his near-saintly refusal to reach over and knock his interviewee out. But his sincere commitment to peace, and his intelligence in analysing the nature of war, is evident in every other moment of this grand, riveting, monumental, unmissable film.