Shubhra Gupta writes: From Mumbai Film Festival, political films you must watch

For the generation used to learning via 'WhatsApp University', well-researched, sharply-voiced documentaries like Indi(r)a’s Emergency are a vital, timely reminder that there can be light at the end of the tunnel

By Shubhra Gupta | November 9, 2023

One of the films I was most eager to watch at the just-concluded Jio MAMI film festival (October 27-November 5) was Anand Patwardhan’s Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (The World Is Family). And that’s not just because it is Patwardhan’s most personal film, focussing on the lives of his parents and close family, but because it is the kind of cinema that is now almost impossible to catch outside a mindfully curated film festival.

In these 96 minutes, you do not just see the filmmaker who has consistently trained his trenchant lens on some of the most significant events which have shaped today’s India. Here he is also a loving son, bowing to the parental patterns of upbringing: As his delightfully acerbic mother Nirmala, one of India’s pioneering ceramists, says, she’s happy to make time for her offspring, not the famous documentary filmmaker. It’s the kind of thing only a mother can say. It makes you smile, while you are also moved to tears, as you are made a witness to their last few years, and moments.

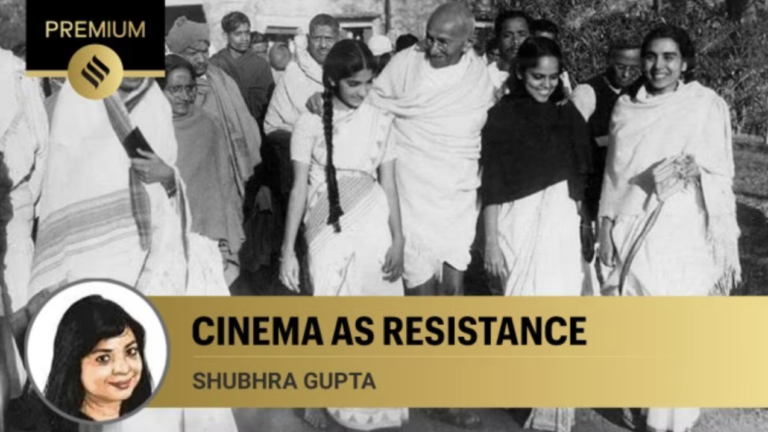

It is also the kind of film where the personal is most political. His family — mother Nirmala, maternal grandfather Bhai Pratap Dialdas, father Balu, paternal uncles Rau and Achyut — were involved, as were so many millions of Indians, in the freedom struggle. We see a very young Nimala, who spent her formative years in Shantiniketan, ranged alongside Mahatma Gandhi and his entourage. We see images of the uncles who took divergent paths — Achyut the rebel who spent many years underground, and Rau a follower of the non-violent movement, who spent years in jail. Balu, whose earthy sense of humour enlivens the film, cackles: I’m the only one who never went to prison. And yet their youth was spent fighting for a freedom that we, the children born after that momentous midnight, received as legacy.

The importance of a film like this cannot be overemphasised. It is a candid, flavourful oral history of the pre-Independence years. It is also a public record of the values those individuals fought for, which are disappearing so fast that you wonder if there will be any memories left, other than the ones being assiduously assimilated and cemented, fashioning a present that is the result of the relentless erasure of the past.

Vikramaditya Motwane’s Indi(r)a’s Emergency, produced by Applause Entertainment, brings back memories of one of the darkest periods of recent Indian history, in which all rights of citizens were yanked off the table by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. But the cleverly-named documentary also reminds you that the Emergency was short-lived; that authoritarian regimes are not forever. Even as political adversaries and fearless journalists were thrown into jail, with Indira’s younger son Sanjay and his thuggish cohorts throwing their weight around with impunity, the wheels to overthrow the Indira-led Congress faction had begun grinding.

The 113-minute film includes rare archival footage and striking animation: A flint-eyed Indira atop an elephant on the historic Belchi march is one such. George Fernandes raising his manacled fists, Jayaprakash Narayan’s famous exhortation of “sampoorna kranti”, and visuals of the “jan sailaab” ( a sea of people) protesting against the excesses of that time, have been nearly forgotten. For this generation, used to learning via “WhatsApp University”, a phrase used in the film knowingly, well-researched, sharply-voiced documentaries like Indi(r)a’s Emergency are a vital, timely reminder that there can be light at the end of the tunnel.

I would add two more in my list of strongly political films which need to be watched widely. Vinay Shukla’s While We Watched, a grim, cautionary account of the whittling away of real journalism in TV news through the eyes of popular former NDTV anchor Ravish Kumar, tells us why we are where we are today. Payal Kapadia’s The Night Of Knowing Nothing, is a hybrid creature, melding fact and fiction in a series of sights and sounds that are beguilingly abstract as well as horrifically real. This is pure, impactful cinema as resistance.

The 2023 edition of the Mumbai film festival, which returned after a four-year pandemic-induced gap, turned out to be solidly programmed, with some of the most feted films from the Berlin, Cannes and Venice film festivals, and a bouquet of Indian cinema, as well as a special focus on South Asia. This last aspect is especially welcome, as it gives us a chance to watch choice offerings from our neighbours — Bangladesh (Mostofa Sarwar Farooki’s Something Like A Biography and Leesa Gazi’s A House Named Shahana) and Sri Lanka (Prasanna Vithanage’s Paradise) amongst others —something we have been missing since the closure of the Osian’s Cinefan film festival in New Delhi.