The Good Doctor of Chhattisgarh

TEHELKA, JULY 14, 2007

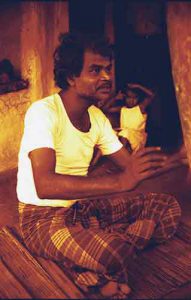

Behind the story of Dr Binayak Sen is equally that of Shankar Guha Niyogi, his friend and inspiration,

murdered in 1991. Anand Patwardhan pays tribute

I first met Binayak Sen in 1986. Shankar Guha Niyogi, legendary leader of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha (CMM), had invited me to screen my film ‘Bombay, Our City’ for the mine workers of Chhattisgarh.

I first met Binayak Sen in 1986. Shankar Guha Niyogi, legendary leader of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha (CMM), had invited me to screen my film ‘Bombay, Our City’ for the mine workers of Chhattisgarh.

Niyogi was no ordinary union leader. Originally a worker in the Bhilai Steel plant, his thinking went far beyond the wage struggle politics of most unions of the day. Although the CMM’s ranks were drawn from marginalised workers who barely earned minimum wages for often life-threatening labour, their optimism and energy was there for all to see. Not only did I witness democracy at work every evening when they gathered to discuss ideological and practical issues, I also saw how innovative their thinking was. Knowing that the predominantly adivasi workforce needed their own symbols of struggle, the CMM revived the memory of a forgotten hero, Shaheed Veer Narayan Singh, a 19th-century adivasi whom the British hanged in 1857 for feeding his people from the granaries of the rich.

In 1981, inspired by Niyogi, Sen and two other doctors came to work among Chhattisgarh’s mine workers. They were instrumental in setting up the modest but impressive Shaheed Hospital, built and maintained with voluntary labour from the miners. By the mid-80s, the hospital had grown from 15 to 50 beds with its own operating theatre. The love, care and pride that went into work at the hospital made it one of the most unique institutions of its kind. Physician and worker alike were literally healing themselves.

The revolution that Niyogi and his comrades envisaged may have borrowed from Marx and Engels, but it also borrowed from Gandhi. It was acquainted both with the failures of the Left as well as with the environmental degradation wrought by the development paradigm practiced world over. In India, by the early 80s, disillusionment with the traditional Left as well as with in-fighting Naxal groups had set in, and there was a search for an alternative vision. Niyogi and the CMM in Chhattisgarh, and Medha Patkar and the Narmada Bachao Andolan in Gujarat, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh seemed the harbingers of a new, green, Left, that would use not armed struggle but grass roots organisation and mass mobilisation as its primary weapon. This Laal Hara (Red Green) was a potent force that everyone hoped would lead us into the future.

The screening of ‘Bombay, Our City’, a film on Bombay’s slum dwellers, was an instant hit. Despite its meagre resources, the union had spent Rs 10, 000 to buy a 16mm projector for the occasion — another example of forward thinking that put real value on workers’ education. Over a thousand workers attended the open air screening that evening and the discussions that lasted long into the night were so lively that the union decided to acquire a print of their own so they could continue to screen the film after I had left. I said I would return but, to my eternal regret, never kept my promise.

History overtook us. People like myself, who had earlier focused on workers’ issues, became preoccupied with fighting the rise of a religious fundamentalism that eventually demolished the Babri Mosque, and went on to engulf the subcontinent in violence and hate. In a sense, Niyogi too became a victim of this rising tide. As the BJP vied for power in the Chhattisgarh belt, it came across a diametrically opposed worldview that had successfully forged class solidarity against all religious divides.

Niyogi and the CMM had other powerful enemies. The workers’ growing confidence had given the union the muscle to tackle social evils like alcoholism. The union took to imposing small fines on workers who drank, secretly returning the amount to the alcoholics’ wives! The shrinking consumption levels hit the liquor mafia hard. Other opponents included labour contractors, who had lost an exploitative livelihood, and an industrialist/ politician nexus that could not tolerate a strong workers’ movement.

On the night of September 27, 1991, Shankar Guha Niyogi was shot dead as he lay asleep in his hut. Those who organised the murder were never punished, although everyone in the area knows who they were. The additional district and sessions court found six persons guilty and awarded the death sentence to the man who fired the gun and life sentences to the other five, including two prominent industrialists close to the BJP, charged with planning and funding the murder. With the BJP in power, the Madhya Pradesh High Court freed the accused, citing lack of evidence.

The orphaned CMM bravely struggled on, ably led by Janak Lal Thakur and Niyogi’s other colleagues. Sen and his wife Ilina stayed on in the area, working both with the CMM as well as in the field of health, and later began work with the civil liberties movement. Sen became General Secretary of the Chhattisgarh unit of the People Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL).

Niyogi’s assassination and the logic of ‘liberalisation’ led to worsening repression of the region’s adivasis and workers. Naxal resistance grew in this vacuum. In response, the state government launched one of its most infamous operations, the Salwa Judum, which arms and trains civilians to form paramilitary vigilante outfits against the Naxals. As PUCL Gen Secy, Sen documented and published reports on the reign of terror unleashed in Chhattisgarh by a nexus of the administration and the paramilitary forces. The State took revenge. They put out a warrant for his arrest alleging that he had met a Maoist leader in jail in Raipur and facilitated an exchange of letters, despite the fact that the PUCL had sought and obtained official permission for this very meeting. On May 14, Sen turned himself in and has been held for over two months now as a Naxalite.

People are rallying to the good doctor’s cause. Support has poured in from across the country. Amnesty International has taken up the case. The medical fraternity in India and abroad has responded, for Sen is that rarest of rare doctors — one who walks and works amongst the poorest and the most deprived. So far, our cries have fallen on deaf ears.

Binayak Sen is a gentle, compassionate man, whom I am proud to have met. If he is to be held a Naxalite for documenting State atrocities, then count me as one too. And count all those thousands who have signed petitions for his release and who will continue to fight injustice in this land wherever it occurs, non-violently, but without fear.

Anand Patwardhan

July 14 , 2007