The Cinema of a Violent Interval: Vivek/Reason

Jyotsna Kapur

On February 18, 1943, as the Germans were losing the war, Goebbels gave what is known as the “total war speech”, in which he asked, “Do you want the war to be still more total, more radical than we can imagine it today?” This was a call for war without limits, as an end in itself. The role of media in such a total war is no longer to distort reality, to create fake news as in propaganda. Rather, it is to destroy the notion of reality itself, to make life itself seem like a movie.

This sense of living in a movie has reached a fever pitch in the current elections in India. Modi has threatened nuclear war, with “we will enter the home of the enemy and destroy it” becoming an election slogan.As if taking their cue from this call, a mob entered a Muslim family home in Gurugram and attacked the family, including women and elders. In Tihar jail, a Muslim prisoner was branded with an Om sign. Pragaya Thakur, who has been in jail for her part in the Malegoan blasts in 2008 traced to the extremist right wing group, Abhinav Bharat, is out on bail for ill health and contesting the elections from Bhopal. We should expect this violent destruction of reality to continue, to see even more extreme flouting of societal norms that ensure the security of life in the coming days.

Yet, cinema is also a technology that is our keeper of history. It can gather evidence and cut through the terror to reveal the making of such terror. Vivek/Reason by Anand Patwardhan is exactly such an exercise. It is an epic film that reveals the shift towards fascism and the resistance to it in the last four years, in both everyday life as well as in our institutions. It places that history in the longer history of human desire for individual freedom and an egalitarian society.

Watch the film from any point and it will still add up. Its epic narrative brings together apparently fragmented moments to reveal larger historical patterns—both the persistence of an authoritarian, repressive, and exploitative ideology (such as Hindutva) and its repeated defeats by democratic and secular forces. It is out of this history that Patwardhan pulls out the hope, that dark as this time may be, it will be, if we pull together, short lived. It draws you into the unfurling of the present moment, giving you hope in struggles that have come before and are now ours to carry on.

Given the nomination of Pragya Thakur, her remarks that she had cursed Hemant Karkare and thus brought death upon him and her non-apology subsequently, I am going to recommend starting with chapter 15 and going on to the end and then starting at the beginning. Through interviews and archival footage, Patwardhan uncovers that Karkare had traced the bomb attacks in Mumbai spectacular between 2002-2008 to the Hindu Right (against the dominant view that they were the work of Islamic extremists)and asks if Karkare was killed for this brave investigation. We see Rohini Salian, the public prosecutor in this investigation, coming to the conclusion that Hindutva forces had deeply penetrated the institutions of the State. The shock of disbelief is palpable on her face. We see Gobind Pansare publicizing S. M. Mushrif’s book, Who Killed Karkare?: The Real Face of Terrorism in India (2011) and connecting Karkare’s death to the bid of the RSS and its allies to turn India into a caste-driven, patriarchal, Hindu fundamentalist state for which “economic development” was unfettered capitalism.

It is profoundly moving, in the light of thakur’s election bid, to go back in time to Hemant Karkare’s funeral procession in the film. The camera notes not only the hypocrisy of the State honors, but also lingers over the flowers that fall on the way side. Humbly, the flowers seem to pay their homage to a brave and honest police officer who had upheld his duty to the Constitution, i.e., to pursue justice equally for all citizens. The flowers are also a metaphor for memory, gathered by the camera for the resistance that has to continue after Karkare’s death. That the time to gather up and piece that memory is upon us so soon is a reminder of how quickly history is moving under our feet. History is made by people and it is heartening that citizens across the country have publicly protested against Pragya Thakur’s remarks on Karkare and her candidature.

Seeing the funeral procession now in light of Pragya Thakur’s candidacy is to be reminded that Karkare is being killed once again, unless we honor his memory and rescue it from the rewriting of history underway. And, the interval to do so is short. It is this election season, after which the struggle will be harder, if the BJP comes to power.

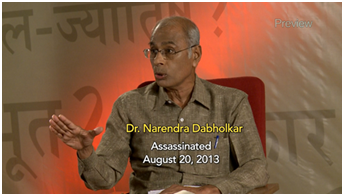

History is human memory. It is how we draw courage to act in the present so that the future may realize the promises of the past and not its cruelties. Vivek/Reason brings to us the immediate past of our present, to help us decide where we want the future to land. One of its important threads is the assassination of Narendra Achyut Dabholkar, Gobind Pansare, M.M. Kalburgi, and Gauri Lankesh. All four were secular progressive intellectuals who held to ideal, inherent in the anti-colonial struggle and written into the Constitution, of India as a secular democracy in which all are radically equal, and freedom lies in the security of all. Anand Patwardhan takes us into the homes of these individuals, shows us how they had lived and worked, and uses the power of cinema to keep their memory alive, and thus the legacy we have inherited.

“I am Gauri” widely present at the rally.

We see the same humanist wish for an egalitarian, plural India in the resolute gentleness of Mohammad Sartaj, whose father, Mohammed Akhlaq, was lynched to death in his own home by a mob in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh on 28th September 2015. Sartaj who is in the Air Force, says, “I am fortunate to be born in this country. There is love among the people” and “only a handful of people” are destroying its fabric. There is grief here, but there is also hope that gives strength to the living.

For the bhakts, the upper caste, middle class Hindu drunk on the image of power (while anxious about their and their children’s future) the Modi regime has been one long immersive movie, addictive for the thrill it keeps dishing out of escape. While we go into a darkened theater, knowing fully well that the movie is unreal—the Modi movie is seen with eyes wide open in everyday life, perhaps most often on a small screen carried in the palm of one’s hand. It promises escape from the increasing violence around gated communities (and the depravities inside) with grand delusions of living in a world power. It also makes it possible to escape altogether from a common sense of humanity, to watch the killing of another in the most brutal way — as an image. When the annihilation of another human being can be enjoyed as a thrill, we have lost our grip on reality.

In the midst of relentless attacks on our minds, senses, and hearts Vivek/Reason offers a moment of pause, analysis and evidence to understand the patterns, and to act with that understanding. It teaches you to think historically, i.e., to connect what we do now with its consequences in the future – and it compels you to take a side. See it. Show it to people who still have the capacity to think with reason, to distinguish between right and wrong. In a short month with the results of this critical election, hopefully, we will see it as a record of a bitterly clouded time, but one in which Indians voted on the side of reason and threw out a regime whose singular promise was ever more spectacular violence.