STORMING THE REALITY ASYLUM

By John Akomfrah

John Akomfrah is an English artist, writer, film director, screenwriter and theorist. He made his debut with Handsworth Songs, which examined the fallout from the Handsworth riots. Handsworth Songs went on to win the Grierson Award for Best Documentary in 1987. John is today one of Britain’s most acclaimed filmmaker artists.

Anand Patwardhan occupies a unique place in documentary filmmaking. Very few documentarists are accepted as auteurs; among those, few are both directors and technicians; and from this elite corps, even fewer come from the so called Third World. Over the last twenty years Anand has consistently taken strands from different documentary filmmaking practices – the Cuban and Latin American Imperfect Cinema style; the more self-reflective political documentaries of Chris Marker and the Dziga Vertov group; the lyricism and attention to detail of the ethnographic school – and put them to work on a series of stunning documentaries.

From Bombay Our City to Father, Son and Holy War, his films have dealt with some of the key questions of our age – the ubiquity of difference in modern lives; masculinity as a source of conflict and power; the absurdities of political power. Except for his first two documentaries, his subject-matter has come from successive political crises in India : the Emergency; the rise of fundamentalism and communalism; the growing political polarisation. He has been holding a mirror to the Indian psyche, to see how it reflects questions of class-belonging, gender and political voice. It is unusual for a documentary film-maker of his caliber to have spent so much time and energy working on what are essentially local questions. The questions acquire an immediacy by being intensely regional in their raison d’etre and their outcome. Paradoxically, by interrogating the local questions over and over again, he has not only arrived at a refined vision of the state of play in Indian culture and society in the nineties, but also in the world at large – forms of fragmentation, the growing alarm with which people protect their ‘identities’, emerging forms of power – all are prefigured in his work.

These are films driven as much by absences as they are by presences. What is absent are agendas imposed rigidly on people, politics or places. Instead, the films are fixed by interests pursued relentlessly, selflessly, ethically. In Patwardhan’s films there is always a sense that what we are watching is a product of an inquisitive impulse – a search for answers through what people say and how they say it, the rhythms of the everyday, the gestures and actions of individuals. Nowhere is his interest in the absence/presence dichotomy used to more effect than in Bombay Out City. In this film he investigates the relation between the culture and life which goes with being an affluent Bombay-dweller and what you do when you are poor in Bombay – what streets you sleep on. The relation between absence and presence is made tangible. Patwardhan interviews a lot of slum dwellers who feel that their condition is not natural – that the reason why they are in that position is because of someone’s neglect, incompetence, or the willful manipulation of their life chances. In this way the rich are evoked as a ghostly presence and their traces are etched deeper as the interviews are intercut with images of facades, the rich going about their daily business.

All his films deal with events which over time acquire political and cultural significance. But there is also the question of aesthetics which is rarely commented on – when people look for aesthetic insights they rarely turn to political documentaries. And yet the way in which Patwardhan investigates the complex relationship between figure and ground – the way he places people in the frame and the space he gives them to express themselves, merit special scrutiny. Through this scrutiny we discover a sustained attempt to think through the ways in which people construct oppressive political languages and motifs for resistance.

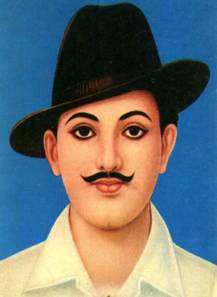

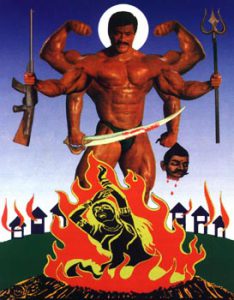

We also begin to see the complex aesthetic and formal questions raised by the attempt to provide the narrative for political activity; the attempt to release events in India from the confines of the stereotype. Central to this deconstructive gesture in his films is the question of repetition. In the repetition of motifs, one glimpses the dark power that images , symbols and motifs acquire in the lives of people. In Father, Son and Holy War, the colour orange signals the Shiv Sena’s public rallies and speech-making. Gradually this colour comes to stand for the circulation of notions of ‘purity’ and ‘impurity’. The process by which the film effects this marriage of political extremism and a particular colour is very complex and yet one is struck in the end by how effortless the whole thing seems. In Patwardhan’s films symbols and icons are both a source of strength and a site of conflict. In Memory of Friends is not simply a biography of a Sikh Marxist who died fifty years ago, but is also about the way in which a number of conflicting groups – the State, Sikh Fundamentalists and fighters for communal harmony – fight over the symbol of Bhagat Singh as a political figurehead in contemporary India. In the film, photographs of Bhagat Singh, both in turban and deracinated, European clothes, are among the images which give clues to the uses and abuses of history. So what starts off looking like a hagiographic exercise on one political symbol from the Indian past becomes a complex film about how people empower themselves and the role icons play in that process. Part of the attraction of the films lies in the fact that Patwardhan lives those events as a filmmaker. He practices what he preaches – a politics of tolerance. In a period of extreme political intolerance, in which a certain kind of politics exists simply to delegitimise other people and their right to be part of the State, the filmmaker enters, willing to confer on all the social actors the same respect. He goes in prepared to listen to people as individuals and they acquire their status as villains – or heroes – after the fact, because of what they say and do. All the films are narratives about Indians talking, or in some cases not talking but killing one another. But crucially they are about their actions, gestures and rhetoric. He observes the everyday, the unfolding fabric of Indian life as a discreet set of activities before these acquire the status of events. He is not interested in stories, but rather in the fragments which make up the story and the role that particular individuals play in it.

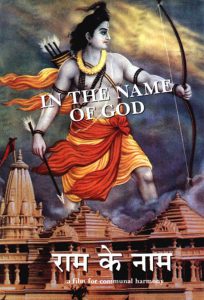

In his films we not only see events acquire the status of the real but get an insight into the complicated process of selection via which particular events attain the definitive status of the real; an insight into the convoluted process of legitimation through which patterns of extreme behaviour become the norm; the Indian reality, condition and fate. Along the way, a few of the mystifying and patronizing platitudes on India – its piety, its fatalism, its extremism – are shown to be ever-evolving historical dramas with living social actors, fragments from a mosaic lived and constructed by social groups. In In Memory of Friends, there’s a man who is a minor player when Patwardhan first meets him – he does not have written on his forehead: “Hero – this man will save the day.” But in the process of observing, filming and interviewing him, it becomes clear to Patwardhan; and therefore to us, that this man has the right ideological and emotional make-up to provide a solid centre for the film. So gradually he gravitates towards him. It is as if he was there to watch this man make up his mind to stand against extremism. This may explain Patwardhan’s fascination with documentary: its privileged rendezvous with history; its uncanny prophetic power; it’s ability to give us an insight into the connections between actions and consequences. In the best documentaries we always glimpse the future. Take a look at Father, Son and Holy War and you’ll see my point. Documentary film-making at its best – Flaherty, Rouch – is a complicated interrogation of reality. The quest to undermine cultural and political assumptions is central, particularly, the stultifying claims of the stereotypical, the cliché-ridden, the teleological. They are supreme acts of deconstruction. They do not try to replace an ossified image of a more real India. Rather, they work with and through the conventional images by seizing hold of them as frames and exploring how their reality is both manufactured and lived. Let us take the assault on the mosque in Ayodhya. It was widely monitored by the media and people thought: how terrible, those fanatics in India, they are always doing things like that. But in the film [In the Name of God] , we watch young men going on a march before they become the mob that tears down a mosque. You hear their opinions and so you follow a trajectory of rage which leads to the outcome. However, we are made aware that many options were jostling to become reality; we get to understand how this option (a mob will attack a mosque ) becomes the logical recourse in a perverse chain of reasoning. In another incident, the central figure in In Memory of Friends was killed by fundamentalists after the film was made. I was all the more shocked because in the course of watching the film I felt that the circumstances which led to his death were not a foregone conclusion; that reality is open-ended. Ultimately this is the value of Patwardhan’s films. They remind us that reality is a many-headed beast – wrestling with it requires both courage and flair.