India, today: Anand Patwardhan’s documentary ‘Reason’ holds a troubling mirror to the headlines

The celebrated documentary filmmaker dives headfirst into the

Hindutva-versus-the-rest divide that has put many lives at risk.

Nandini Ramnath | Sep 09, 2018

The most important Indian title to be screened at the ongoing Toronto International Film Festival isn’t a feature from Bollywood, but a searing independent documentary by one of the most celebrated practitioners of the form.

Anand Patwardhan’s Reason (the Hindi title is Vivek) was premiered at Toronto on Saturday. Divided into eight chapters and clocking in at four hours and 20 minutes, Reason is easily one of the most important documentaries to emerge in the Age of Modi. The film dives fearlessly into the debates that hit the headlines with troubling regularity: the murders of rationalists and attacks on activists critical of government policy; the emergence of shadowy Hindutva organisations such as Sanathan Sanstha and Abhinav Bharat; hyper-nationalism; the attacks on Muslims and Dalits in the guise of cow protection; the attempts to rewrite history; the mainstreaming of radical Hindu beliefs and the attempts within the government and outside it to transform India into a Hindu state; the attacks on protesting students in universities.

Reason presents “empirical evidence of what is happening to India today”, says the official synopsis. “The overall argument of the film is made more gradually as we understand the ideological forces that have been at play for centuries.”

The film’s premiere in Toronto comes in the wake of the raids on and arrests of activists and intellectuals on the dubious charges of supporting a Maoist conspiracy to assassinate Prime Minister Narendra Modi and overthrow the Indian state. Although the raids on dissidents such as Dalit scholar Anand Teltumbde and the arrests of civil rights activist and lawyer Sudha Bharadwaj and others took place after Patwardhan had completed his film, this has been foreshadowed by the events that he captures in Reason.

There is a sense of raw immediacy in the braiding of numerous interviews, television clips and internet videos and footage of rallies, protests marches and lectures and public meetings by proponents of both sides of the debate.

Right here, right now

A recurring motif in Reason is a dramatised depiction of an unseen murderer on a motorcycle, prowling for fresh victims in the dead of the night. The first of the eight chapters lays out the raison d’etre for the film: the murder of anti-superstition activist and rationalist Narendra Dabholkar on August 20, 2013, which was followed by the killing of Communist Party of India leader Govind Pansare on November 20, 2015. Dabholkar and Pansare were, in different ways, thorns in the side of the Hindutva establishment, pricking claims of upper-caste supremacy and exposing anti-minority sentiment, the appropriation of historical figures and the advocacy of divine solutions to problems with economic and social roots. Both men wrote and lectured extensively, and tirelessly worked with local communities. Both paid with their lives, but their messages continue to resonate, as moving interviews with family members and followers prove.

Why did Dabholkar and Pansare – and academic MM Kalburgi and journalist Gauri Lankesh – have to die? Patwardhan argues that rampaging Hindutva, which has spread its tentacles to all corners of society and the upper levels of the government in its mission to convert our secular republic into a narrowly-defined Hindu nation, poses the biggest threat to Indian values. “That such an ideology should come to power today is a clear and present danger to all who believe in democracy, social justice and equality,” Patwardhan says in his director’s note.

Rampaging Hinduvta

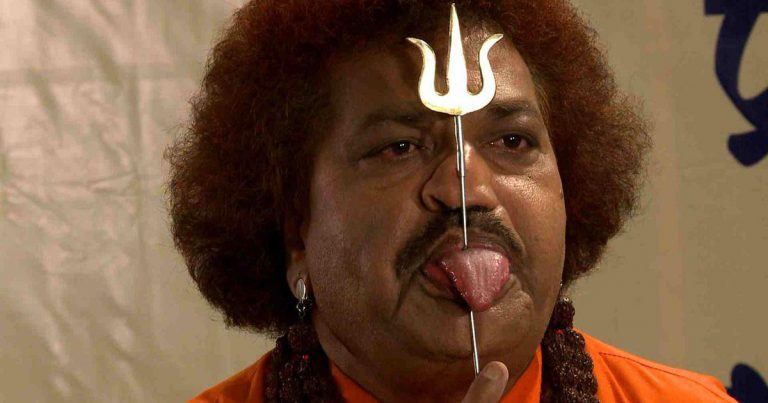

Through the sections on the concept of “Sanatan dharma”, or eternal faith, the refashioning of Maratha warrior Shivaji as a Hindu icon, and the activities of the extremist Sanathan Sanshta, whose members have been linked to the Dabholkar, Pansare and Kalburgi killings, Patwardhan rings alarm bells about the rise of militant Hindutva.

“More than a monolithic religion, Hinduism is a dynamic composite of indigenous cultural practices combined with those borrowed over the ages from passing streams,” Patwardhan says in his director’s note. “Sanatan, Aryan, Vedic, Hindutva on the other hand is a Brahminical (originally emanating from a powerful priest caste) project of supremacy, which recruits the powerless in an endless war against imaginary demons. Invoking such a war gives its instigators absolute control and total impunity.”

This deadly dance between what Patwardhan terms “divinity and reason” plays out in a variety of ways. Dalits and Muslims are attacked by cow fanatics in Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat even as the Dalit movement for land rights gathers steam. The suicide of PhD student Rohith Vemula at Hyderabad Central University reveals the demonisation of Dalit assertion and the gameplan of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s student wing, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad. On other campuses, including Film and Television Institute of India and Jawaharlal Nehru University, ABVP leaders attempt to divide students into patriots and traitors.

This deadly dance between what Patwardhan terms “divinity and reason” plays out in a variety of ways. Dalits and Muslims are attacked by cow fanatics in Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat even as the Dalit movement for land rights gathers steam. The suicide of PhD student Rohith Vemula at Hyderabad Central University reveals the demonisation of Dalit assertion and the gameplan of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s student wing, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad. On other campuses, including Film and Television Institute of India and Jawaharlal Nehru University, ABVP leaders attempt to divide students into patriots and traitors.

Patwardhan’s inquiry extends to the terrorist attacks in Mumbai in 2008. Among the victims of the audacious assault by Lashkar-e-Toiba terrorists was Hemant Karkare, the head of the Anti-Terrorist Squad for Maharashtra. Karkare had been investigating the role of Hindu radicals in bomb blasts, which was initially blamed on Islamist groups, and was heading the probe into the 2006 Malegaon blasts, which was alleged to have been carried out by the Hindu radical group Akhand Bharat. The film wonders, not very convincingly, if there is more to Karkare’s death.

One insightful chapter is devoted to the attempts to transform Hindutva ideologue VD Savarkar into a nationalist hero and to have his portraits and statues installed in public places. In this section, as in other places, Patwardhan contrasts what the history books tell us about Savarkar’s opposition to the inclusive values of the Indian freedom struggle and the present-day efforts to pass off his beliefs as patriotic sentiment.

Through Reason, Patwardhan returns to themes explored in Ram Ke Naam(1992), which is about the emergence of Hindutva on the national stage and the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in 1992, and Father, Son, and Holy War (1995), a meditation about the ideological foundations of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh and Hindutva’s cult of masculinity. In Jai Bhim Comrade (2012), Patwardhan placed Dalit folk culture within the larger framework of Dalit resistance and the often-violent pushback by upper-caste forces.

As in all his films, beginning with Waves of Revolution in 1971, about the popular movements against Indira Gandhi’s regime in the mid-1970s, Patwardhan pounds the streets and puts himself on the frontline as he searches for answers. Alongside conversations with victims of injustice and institutionalised prejudice that are conducted at the places where crimes or protests are taking place, Patwardhan turns his camera on the antagonists in his films. He gets them to implicate themselves by asking them to explain their ideological positions, and often confronts them with the other side of the argument.

In Reason, the 68-year-old filmmaker wrestles down ABVP members and RSS foot soldiers with questions about Savarkar’s hazy involvement with the freedom struggle and the links between the RSS and Mahatma Gandhi’s assassin, Nathuram Godse. The section on the Sanathan Santhsa headquarter in Goa’s Ramnathi village reveals the discomfort and anger of local residents at the radical organisation’s shadowy activities and its attempts to peddle a narrow view of Hinduism.

At a press conference in Mumbai by the Sanatan Sanstha to disavow any involvement in terrorist activities, one of the men on the dais threatens to physically assault Patwardhan without realising that the filmmaker is actually in the audience. Since then, police investigations have alleged that Sanatan Sanstha sympathisers are involved in a plot to carry out blasts in Mumbai, Pune, Satara, and Nallasopara.

At a press conference in Mumbai by the Sanatan Sanstha to disavow any involvement in terrorist activities, one of the men on the dais threatens to physically assault Patwardhan without realising that the filmmaker is actually in the audience. Since then, police investigations have alleged that Sanatan Sanstha sympathisers are involved in a plot to carry out blasts in Mumbai, Pune, Satara, and Nallasopara.

Reason will challenge the Indian censor board and self-styled nationalists like no other Anand Patwardhan documentary. The very forces that he critiques throughout his narrative will work hard to ensure that Reasondoes not get shown in India. Questions will be raised about the wisdom of the conspiracy theories about Hemant Karkare’s death. Patwardhan’s commitment to the values enshrined in the Constitution of India will be challenged.

And yet, the uncomfortable truths raised in the film about the state of the Indian democracy will not go away, as the arrests of the five activists in August prove. For the same reasons that it may not be widely screened across the country, the documentary demands to be seen, absorbed and debated.