Anand Patwardhan’s Vivek is on the increasing radicalisation of contemporary India

Namrata Joshi | Sept 14, 2018

The filmmaker’s method is simple: Put a camera and mic to people and they will reveal themselves

Anand Patwardhan’s sprawling 261-minute, eight-chapter documentary Vivek (Reason), on the increasing radicalisation of contemporary India, didn’t begin its journey on a storyboard. “None of my films start with a very clear idea of what’s going to happen. Things just unfold. I document, and then, when I am editing, I see the patterns emerge. You start understanding the linkages,” says the veteran filmmaker with seminal works like In The Name of God (1992), Father, Son and Holy War (1994), War and Peace (2002) and Jai Bhim Comrade (2011) behind him.

Whether social inequity or atrocities against Dalits, cow vigilantism, love jihad orrefashioning Shivaji and rewriting history, or witch-hunting in the campuses — they go back to the same roots.

Patwardhan started making the film after activist and CPI member Govind Pansare was killed; he shot and edited it over four years. “I also did a study of Dr. Narendra Dabholkar who was killed two years before Pansare. While the film was being made, Prof. M.M. Kalburgi and journalist Gauri Lankesh were also killed,” he tells me at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) after the film’s press screening. The ideology that killed Gandhi also killed Dabholkar and others, the film asserts, as a motorcycle vrooms away on the dark screen.

“You can’t keep up with the ugliness and violence that is happening in our country,” Patwardhan says. “Things are happening all the time. At some point you say that this is what I have filmed and we must start showing it.”

For someone who follows news closely, the research and the shooting went hand in hand. He also compiled a lot of footage that he hadn’t shot himself. For instance, Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti provided him much of the material on Dabholkar.

Fully present

For Patwardhan, there is no such thing as neutrality while making documentaries. “That is a pretence. Like you as a journalist bring your own ideas into what you are writing, a filmmaker also looks at the world with their own perspective. Any claim of “objectivity” is always false so it’s much more honest to wear your views on your sleeve. Clearly, if Amit Shah made this film he would see the same incidents in a different light. Vivek, according to him, is an honest film with a point of view.

So, far from subsuming himself in the film’s narrative, Patwardhan is actively present in it as the filmmaker, out on the streets, probing, questioning, even getting confrontational with the hardliners. “From my perspective I see these people as the killers of Mahatma Gandhi. They are just appropriating his glasses and broomstick but they have killed both, the man and his ideas.”

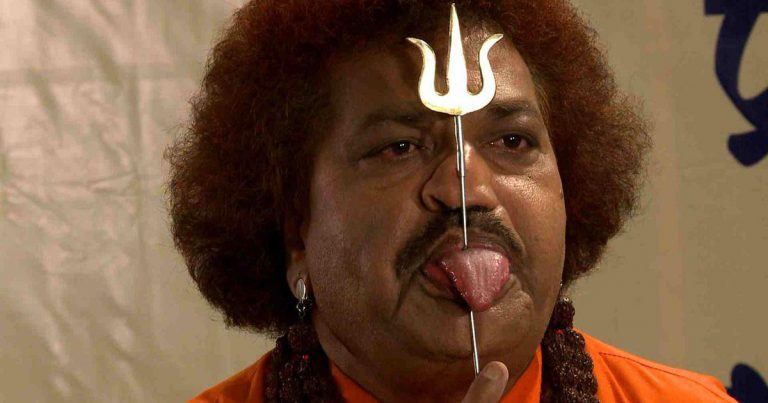

His method of filming is simple. Put a camera and microphone to them and they will reveal themselves as long as you are able to ask critical questions. “We have hundreds of talk shows but they no longer ask difficult questions,” he says. So he puts people on the spot. “They don’t even know their own history. Apart from Savarkar who else fought for freedom in your parivar I asked one of them; he couldn’t come up with a single name.”

When he asks someone else about RSS leader M.S. Golwalkar’s admiration for Hitler, he flatly denies it, saying he has read all of Golwalkar. “Apart from rewriting Gandhi, Ambedkar and wiping out Nehru, they are even sanitising their own ideologues. They tried to clean up Golwalkar. Their reprinted copies don’t have the dark (pro-Nazi) bits. Luckily their earlier editions are on record.”

Some interactions get aggressive. “I didn’t plan those moments. They happened. I didn’t go wanting to provoke them. I went to shoot and saw them carrying a poster with Gandhi and Ambedkar and I asked what’s going on. How can you claim them?”

The constant questions

Patwardhan has always been confrontational and questioning. He has made films on Jayaprakash Narayan’s Bihar movement and against Emergency. “We are critical voices; we can’t do chamchagiri (sycophancy),” he says. Emergency, he says, “had a more dramatic resistance to it. It was declared and open, so people resisted it. Now what is being done to the country’s fabric is more insidious. The character of people is being changed, their minds are being poisoned. And it has the backing of the corporate class who won’t complain as long as the stock market bubble doesn’t burst.”

There is much that is depressing and disturbing in the film. And some bits that are highly contentious — like the theory behind the killing of Mumbai ATS chief Hemant Karkare. “We put many indisputable facts on the table, people put their lives on the line to speak the facts they were privy to, knowing this would bring them no good. I salute their courage. Surely an impartial re-investigation is apt?”

There is hope in the fearlessness of many dissenting voices from the margins. Without dissent “you will be dead before you are actually dead,” says Patwardhan.

There are also simple heartwarming stories — of Shaila Dabholkar and Uma Pansare — the wives of the assassinated heroes and their continued commitment to the idealism that is the bedrock of their families. There is Pansare’s associate showing his photograph in his wallet, saying “I keep sir in my wallet”. And the grieving son of Mohammad Akhlaq, who was lynched, saying it is difficult to find any other country like India.

Vivek has been translated as Reason in English. Patwardhan, however, feels ‘vivek ’ means much more than just reason. It includes wisdom and humanism, and together with reformism and resistance, it can forge a way out of our current social and political quagmire.