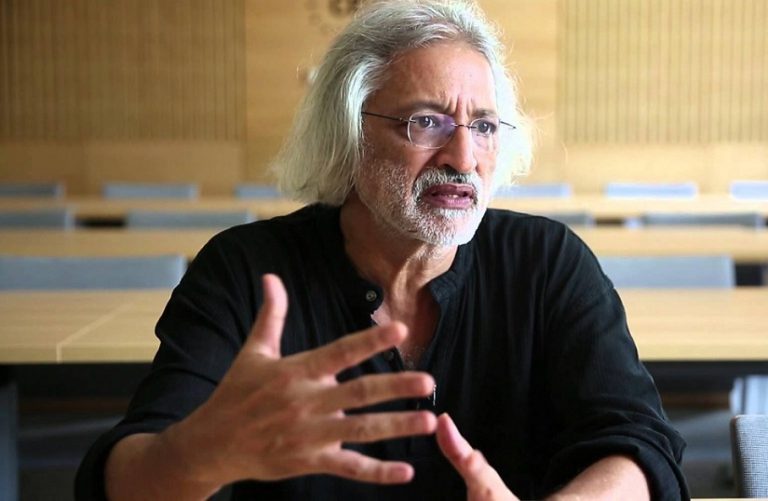

TIFF 2018: Anand Patwardhan’s Vivek

is an exhaustive commentary

on a diminishing democracy

Vivek, divided into eight chapters, is an exhaustive commentary on the way an orthodox,

militant and right-wing Hinduism has taken over every bastion of democratic thought in India.

Bedatri D Choudhury | September 25, 2018

Anand Patwardhan’s latest 261 minutes-long documentary in eight parts is called Vivek, the title in English reads Reason. Given the decline of both reason and conscience (which is perhaps a more fitting transliteration of “vivek”) in contemporary India, amidst rapid saffronisation, both titles fit the film perfectly. Vivek, divided into eight chapters, is an exhaustive commentary on the way an orthodox, militant and right-wing Hinduism has taken over every bastion of democratic thought in India. A searing critique of the Hindutva politics spearheaded and amply aided by the present Indian government, and of past governments who have been inept in quelling it, the documentary is a courageous and diligent takedown of the kind of politics we see around us in India today.

None of what we see in Vivek is news to us; starting from the murder of rationalists like Govind Pansare, MM Kalburgi and Narendra Dabholkar, to the attack on public universities like Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and Hyderabad Central University (HCU), and the atrocities committed on Dalits and Muslims, Patwardhan’s documentary is a collection of headlines we have all read through the last few years. Yet, to see them lined up in these neat chapters, all gathered in one place, is an uncomfortable reminder of the terrible and dangerous times we live in. Systematically, Patwardhan’s narrative takes every act of Hindutva violence that has gone unpunished — his camera travels across the country to Una in Gujarat during the Dalits’ strike, to Dadri after Mohammed Akhlaq’s murder, to Hyderabad after Rohith Vemula’s State-compelled suicide, to the JNU campus after the arrest of student activists, to Goa’s Ramnathi village where the very dubious and dangerous Sanatan Sanstha houses its headquarters, and further and beyond. As in his previous films, Patwardhan tirelessly and fearlessly documents every ominous step the Hindutva juggernaut takes through the country as it other-ises every person who is not a Hindu, a Brahmin, or a Hindutva sympathiser. It is most definitely a rampage aided by fake news, a complete breakdown of reason, and a total wiping out of a collective conscience; a rampage that can perhaps only be mitigated through the counter-narratives of films like Vivek.

If watching a film like Vivek is difficult, one must realise how dangerous making it is, especially in times when activists are being subjected to senseless violence and scrutiny. In a scene where Patwardhan stands filming, a Sanatan Sanstha member openly threatens him, wanting to break his bones. While Patwardhan draws a line through every act of State-sponsored terrorism and presents to us the very violent founding logic of the Hindutva modus operandi, he also travels far and wide to document every voice of dissent that is emerging, amidst growing threats, in India; he speaks to Jignesh Mevani, Kanhaiya Kumar, Umar Khalid, Sheetal Sathe, and the family members of the people who have been killed by militant Hindu forces. Within a country where men like Savarkar are being pitched as heroes, Patwardhan’s lenses are constantly trying to rewrite that flawed narrative that lionises corrupt and morally bankrupt men. This film, like his other ones, is constantly urging the audience to recognise the real heroes who are actually trying to uphold the tenets of democracy India was founded upon. It is asking us to stop and hang our heads in collective shame when Akhlaq’s son, Mohammad Sartaj, says he loves India and considers himself fortunate to be living here. It is constantly reminding us to go looking for our missing reasoning powers, and then using them to reinstate the conscience that we, as a country, appear to have lost completely.

Sitting in the audience, it is easy to sigh over what one sees in the film and then leave with a heavy heart, without realising how we all perhaps contribute to the vicious regime of a government that openly aids terrorism. In scene after scene, Patwardhan documents how organisations like Sanathan Sanstha have been involved in carrying out the Malegaon blasts, and how the whole Hindutva pogrom has aided it, with the government sitting mum on the violence they have orchestrated. In a country where Whatsapp messages trigger mob lynchings, films like Vivek raise a finger at everyone who, through seemingly harmless acts like forwarding messages, propagates fake news and creates an environment of paranoia. Of course, the film shows us everything that’s going on, but it highlights, very sharply, the fact that militant Hindutva politics has only been able to garner so much support because a large number of people have stopped using their sensibilities to judge and reason with the State. It also brings to focus how blindly people have chosen outrageous media outlets, that thrive on sensationalising and scandalising events, to form their opinions and beliefs.

The most immediate message that the film wants to convey, is the need to question the hyper-nationalism that unfortunately gets normalised through regular lynchings, cow vigilantism, and attacks on students and minority groups. It is perhaps the most genuine and most important depiction of the times we live in. It is a lesson in history that shows us, through solid research and not “alternate facts”, how the Hindu right wing through outfits like Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), Sanatan Sanstha and more, have only perpetrated violence, discord and bred communal conflict right from its inception, through all of history. These are outfits that have essentially gained power through proliferating lies and it is through producing a web of lies and hate, that they continue to terrorise and kill.

The film will make the audience feel a lot of things, ranging from fear to sadness that is sometimes peppered with wee bits of hope, but its main intent is to raise a caveat and encourage people to use their faculties of reason and logic to question and debate every narrative the right-wing State feeds them. One is not sure how much a documentary can change the minds of people who have very consciously devoted themselves to the cause of terrorising every dissenting entity, but one hopes that it is able to expose the absolutely corrupt ways in which such operations function in a land that calls itself the world’s largest democracy.