India’s Leading Documentary

Filmmaker Has a Warning

By Abhrajyoti Chakraborty

Published Dec. 1, 2020

In Jaipur one afternoon last fall, the filmmaker Anand Patwardhan sat in a booth outside an auditorium, waiting to screen his latest documentary, “Reason.” These showings, Patwardhan had written to me earlier, were “semi-clandestine” — partly out of a fear of right-wing vigilante groups and partly because, even now, two years after premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival, “Reason” remains officially unreleased in India. Patwardhan had yet to submit the film to the Central Board of Film Certification, a federal body that routinely demands cuts to Indian movies before awarding them a rating, which is why it is commonly known as the Censor Board. Now Patwardhan sat selling DVDs of his previous films for 200 rupees, less than $3 apiece, besieged by fans asking for selfies at the booth. “I want my films to be seen,” he said. “Money is the least of my worries.”

Over four hours, “Reason” documents how the world’s largest democracy has plunged into a majoritarian abyss since the Bharatiya Janata Party, or B.J.P., came to power in 2014, and Narendra Modi was voted in as the prime minister. With testimonies from witnesses to mob lynchings, stories of college students driven to suicide by intense right-wing ostracism and interviews with Hindu nationalists willing to defend the frequent murders of journalists and activists, Patwardhan contradicts the narrative that the B.J.P. routinely projects to the country’s 900 million voters: a story where, under Modi, India is at last starting to fulfill its potential, more than 70 years after independence. A week before the parliamentary elections last year, 16 clips from “Reason” were anonymously posted on YouTube. Watching them I grew afraid, not just for the fate of the film at the hands of the Censor Board but also for Patwardhan.

In one scene, a lawyer representing the Sanatan Sanstha — a Hindu extremist organization linked to four assassinations in the last seven years — openly threatens Patwardhan at a news conference. The lawyer is angry with Patwardhan for attending a protest rally in Mumbai following one of the assassinations. “Why didn’t the police break Patwardhan’s bones?” he asks. The next moment we see a man in a black tunic, filming the scene in the same room, raising up his hands to talk. “I am right here,” Patwardhan says. “If you want to do something you can.” The viewer is left wondering if Patwardhan is next in line to be killed.

“In many ways, this is worse than the Emergency,” Patwardhan told me. He was referring to the 21 months from 1975 to 1977 when Indira Gandhi, then the prime minister, had suspended civil liberties after a court invalidated her re-election, citing corruption. “Things were clearer then. People were put in jails, newspapers were censored. We could resist that. But now our minds have been infiltrated. There is no need for any coercion. We have been conditioned into a false sense of normalcy. Most of us don’t know how bad things are.”

A month after Modi was re-elected, in June last year, the Indian government denied Patwardhan permission to screen “Reason” at a film festival in the south Indian state Kerala. In August, six college students were reportedly arrested in Hyderabad for organizing a screening of another Patwardhan documentary, “In the Name of God.” Across the country, screenings of “In the Name of God” were planned in solidarity against the arrests. In Delhi, members affiliated with the student wing of the B.J.P. tried to disrupt a classroom screening at Ambedkar University. “A group of men barged into the room,” one of the students who had organized the screening, Sruti M.D., told me. “They turned on the lights, shouted slogans and kept saying that the film offended their Hindu sentiments. Somehow the guards made them leave. But they continued kicking the doors of the classroom outside after the screening resumed. It was scary. They cut off the power to our room. We had no choice but to watch the film in the end on a laptop with Bluetooth speakers.”

This is not an unfamiliar battle for Patwardhan. For more than four decades, he has been India’s leading documentary filmmaker, tracking the country’s unraveling from its pluralist post-Partition ideals to a Hindu hegemony. His films have portrayed Mumbai’s slum dwellers, the cruelty of the caste system, the arms race between India and Pakistan, but they remain unseen in large parts of the country because of their inconvenient themes. With almost every documentary he has made, Patwardhan has had to approach a court to ensure it is shown without restrictions. His films have won publicly funded awards at the same time as efforts have been made to limit their viewership. They reflect, both in their reception and content, the schizophrenic nature of Indian democracy.

The screening in Jaipur was to take place at the end of a leftist writers’ conference. Patwardhan passed me a copy of the conference schedule: “Reason” was not on the list. But it was unofficially understood that at 5 p.m., the documentary would be screened after tea. Five became 6, then 6:30, then 7, and writers were still going on about the grimness of the situation in the country. Barely a month earlier, the Muslim-majority state Jammu and Kashmir was placed under indefinite lockdown and its special status under the Indian federation, which had afforded it a degree of autonomy, was revoked. Local politicians were arrested; phones and internet lines were still cut off; there were reports of thousands of civilians being detained. Meanwhile, in Assam, another border state, nearly two million residents had been stripped of their citizenship in an effort to identify undocumented migrants. There seemed just too much to discuss.

Sometime after the screening began, the sound system broke down. The audience, until then attentive, quickly exited. When the film resumed after 20 minutes, no more than 10 or 12 people were still in their seats.

“The breakdown was deliberate, you know,” Patwardhan told me later that night, over dinner. For a moment I was reminded of the disrupted screening at Ambedkar University, of men banging doors and cutting off the power in protest. But a country’s slide into intolerance is rarely so dramatic: Norms don’t always collapse overnight; they corrode against the background of everyday life. “No, I meant the sound technicians,” Patwardhan continued, as if reading my thoughts. “I think they forced the interruption. It has been a long day — they probably wanted to go home.”

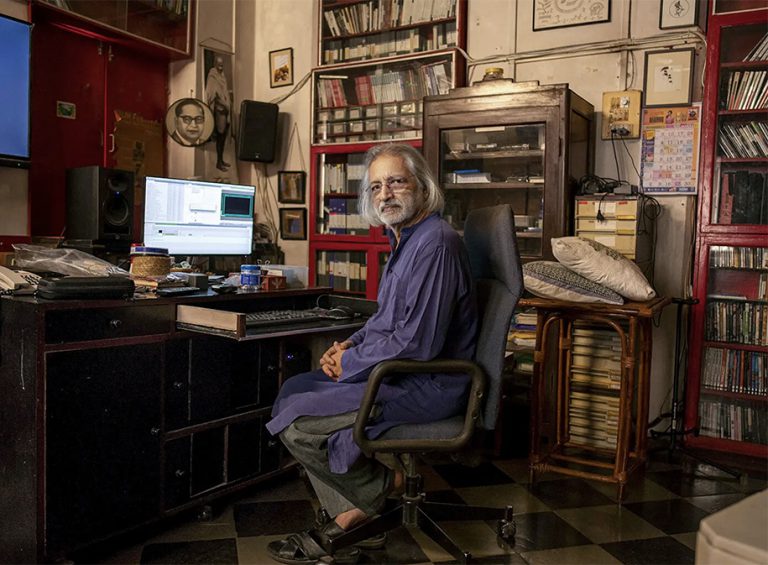

At 70, Patwardhan is nearly the same age as independent India, and his appearance — long hair, youthful face, leather strap sandals, loose homespun cotton tunics — is at once haphazard and hopeful, not unlike the promise of a new republic. India’s promise was embodied by three founding fathers: Gandhi, with his message of nonviolence, his deep distrust of Western civilization and his distress in his last year, after witnessing the bloodshed of the Partition; Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, a liberal who called dams and power plants the “temples of modern India” and saw industrialization as the best way forward; and Bhimrao Ambedkar, who was born a Dalit — the former “untouchables” who occupy the lowest rungs of the caste system — and rose to become one of the main authors of the country’s constitution, embracing Buddhism in protest against Hindu society’s inherent disparities. Despite their different priorities, the three shared a vision of India that preserved its historic heterogeneity, where secularism meant not an absence of religion from the public sphere but a benign, if sometimes mushy, affinity for all faiths.

Patwardhan grew up a beneficiary of that promise. His father worked in publishing; his mother was a renowned artist and potter. His uncles — one a Gandhian, another a socialist — were frequently in prison during British rule. His aunt had escaped from jail into Nepal and briefly undergone weapons training. According to Patwardhan, Ambedkar had even stayed for a while in their family house. Still, Patwardhan doesn’t recall his early years with enthusiasm. “I was a spoilt child,” he told me, “very frivolous, very privileged.”

Though India’s freedom struggle loomed large in his family life, growing up Patwardhan was oblivious to politics. He studied English literature at Elphinstone College in Mumbai, where he remembers not participating in anything: “I bunked too many classes, spent too much time in the college canteen,” he said. But in 1970, a scholarship to attend Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., transformed him overnight into an activist. “Suddenly I was attending Black Panther rallies, going to jail for anti-Vietnam demonstrations,” he said. Angela Davis and Abbie Hoffman had both graduated not too long before. Patwardhan recalls that two students were wanted by the F.B.I. during his time there. Sundar Burra, a close friend of Patwardhan’s at Brandeis, remembers the insurgent mood on campus. “We had a joke about a certain professor,” Burra told me, “that your grades in his course depended on the number of times you’d been to jail with him.”

After graduation, Patwardhan overstayed his visa to volunteer for the labor organizer Cesar Chavez in California. He returned to India and worked for two years with a nonprofit in a remote village. In 1974, he was asked to film a protest march led by students and farmers against the corrupt Indira Gandhi government. He borrowed two cameras, bought some outdated film stock, recruited a friend as a cameraman and set off for Bihar, still one of India’s poorest states, where the protesters had planned a huge rally.

Just after he had transformed the footage of the protests into “Waves of Revolution,” his debut, Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency. Patwardhan cut the film print into two or three pieces, smuggled them abroad with different friends and then secured a fellowship to McGill University in Montreal for a master’s degree, where he managed to reassemble the film. Away from the country during a period of authoritarian repression, he traveled across North America and Europe, showing the film to universities and film clubs, raising awareness about the collapse of democracy back home.

At underground screenings of the film in India, audience members had to be individually vouched for. If discovered, Patwardhan wrote later, “at best … the film would have been confiscated and at worst, jail for all those present.” Most documentaries in India were then produced and distributed by the government, Soviet-style, so the idea of a director going around screening his anti-establishment offering was at once both risky and appealing. Sanjay Kak, a fellow filmmaker, remembers attending a screening of a Patwardhan documentary 40 years ago. “Anand arrived with a 16-millimeter movie projector,” Kak told me, “and a stack of newspapers to cover up the windows of the screening room. I thought, Who is this man traveling with a projector to show his own film?

In India, the Modi years are often spoken of as an “undeclared Emergency.” But something more enduring, a fundamental reimagining of the nation as a homeland for Hindus, appears to be afoot. The country’s roughly 200 million Muslims are, in this narrative, seen first as suspects, then citizens. They are accused of killing cows for meat — many Hindus consider the cow sacred — and cornered in public places to prove their patriotism. Muslim men are beaten up over Facebook posts and blamed for everything from the country’s “overpopulation” to luring away Hindu women through marriage. Many cities and landmarks that reflect India’s Muslim heritage have been renamed. Some school textbooks now glorify Hindu myths and paint the subcontinent’s Muslim rulers in a barbaric light. Incendiary WhatsApp rumors mislead the country’s overwhelming Hindu majority into viewing themselves as somehow under siege. Hate crimes against Muslims as well as other minorities have gone unprosecuted for years. Dissenting artists and academics are told to “go to Pakistan” if they don’t like the way things are.

The rise of the B.J.P. and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, or R.S.S. — a militant organization devoted to making India a Hindu state and its minorities second-class citizens — has also been accompanied by mounting attacks on freedom of expression. Publishers have been pressured to withdraw books critical of Hindu figures. Reporters have been harassed, silenced with spurious criminal cases and in some instances killed. Policemen have gone on rampages inside university campuses. More than 50 writers and filmmakers, including Patwardhan, have returned their state awards in protest. A few weeks ago, the government passed an order to regulate online news and streaming content, stoking fears of more censorship.

“Reason” tries to cover every aspect of this traumatic transition, the wanton displays of coercion and cruelty that increasingly characterize what Modi’s supporters gleefully call the “New India.” The larger story Patwardhan tells in the film is of a revival of the psychosis of Partition, when the subcontinent was divided by the British into India and Pakistan along explicitly religious lines. More than one million people died in the resulting violence, and, according to some estimates, more than 15 million were displaced. Democracy in India was never quite robust — Ambedkar thought the Indian soil was “essentially undemocratic” — but never before have all its organs seemed so fragile. The liberal opposition is weak, undecided and of two minds about being perceived as hostile to the B.J.P.’s bellicose nationalism. Newspapers, bound to the government for advertising revenue, have suppressed stories critical of Modi and the B.J.P. Skeptical news anchors have been arbitrarily pulled off the air. TV networks that refuse to toe the line have been investigated for laundering money from abroad. Bank accounts of human rights organizations have been frozen. Citizens have been jailed for lampooning Modi online. Activists are routinely scorned as traitors. Policemen have falsely implicated victims of right-wing violence. Bollywood celebrities tend to stay silent, fearing censorship and reprisals before a big release. Any decision that the government takes is spun overnight on television and social media as an expression of the popular will, the logic being that Modi won the parliamentary elections, not once but twice.