A CINEMA OF SONGS AND PEOPLE: THE FILMS OF ANAND PATWARDHAN

12–28 JULY 2013 | TATE MODERN FILM

Rarely viewed in Britain, the films of Anand Patwardhan represent

one of the most important achievements in documentary cinema

This season brings contemporary audiences into contact with an astonishing body of work whose profound commitment to radical change offers an experience like few others in contemporary cinema. This comprehensive retrospective, the first to be devoted to the major works of Patwardhan in London, devotes long overdue attention to a giant of cinema whose films inaugurated the independent documentary moment in India in the mid-1970s.

Patwardhan’s films focus upon the wounded polity of contemporary India, continually returning to the painful entanglements of nationality, warfare, religion, impoverishment, community, gender, caste and class.

Born in 1950, he studied Sociology at Brandeis University in Massachussets at the end of the 1960s; after college, he worked with the Farm Workers Union in California with Cesar Chavez, who later appeared in A Time to Rise, his 1981 documentary film on Indian farm labourers in British Columbia. He directed his first film in 1974, during a moment of intense upheaval in India. Waves of Revolution 1975 captured the excitement of the anti-corruption mass movement in Bihar, Northern India throughout 1974 and the repression imposed by Indira Gandhi when she declared the state of emergency in 1975. Such a film could never have been directed under the auspices of the state-run Films Division that produced and distributed documentaries in India. Prisoners of Conscience 1978, Patwardhan’s first film to be widely screened in India, emphasised the widespread policies of arrest and torture both before and after Indira Gandhi’s dictatorship while Bombay: Our City 1985, his deeply felt documentary, depicts Bombay’s millions of pavement dwellers and their daily struggle for survival in the face of slum clearance.

In the 1990s, Patwardhan embarked upon a series of films addressing what Geeta Kapur calls the ‘unmaking of secular India.’[fn]Geeta Kapur, ‘Globalization: Navigating the Void’ in When was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Practice in India, Delhi 2001, The growing communalism of Indian politics, ‘communal’ being the term used in India for sectarian and increasingly fundamentalist religious communities, was and indeed remains, in direct conflict with the secular, socialist traditions that inform Patwardhan’s aesthetic and political thinking.

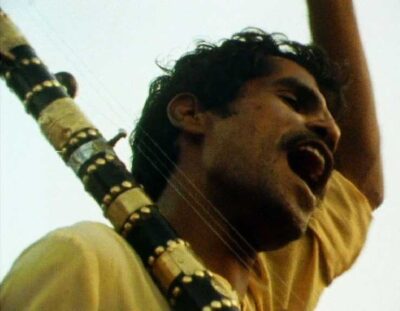

In response, Patwardhan has gradually developed a range of aesthetic methods capable of puncturing the aggressive defenses common to all fundamentalisms. These methods stem from his style of shooting. As well as editing his films, Patwardhan also operates the film camera and at the same time, conducts interviews. In the frame, he tends to focus upon a single face within a crowd, drawing its forms of speech and varieties of gaze towards his lens. In these moments can be seen the young fanatic that expresses himself with the freedom of the mob and the upper class that voices self-congratulation in the tone of self-pity.

From the 1990s onwards, Patwardhan’s films have increased in their period of gestation. War and Peace 2002, his incisive documentary on the varieties of thermonuclear theology in India, Japan, USA and Pakistan took four years to complete while Jai Bhim Comrade 2012 took fourteen years to complete. What is striking is how War and Peace and Jai Bhim Comrade move between the quietude of the solitary interview, the noise of the crowd interview and the focus on the activities that constitute the mechanisms of the media event. Patwardhan’s films alert you to the format of public events staged for television and newspapers; the festival or the rally sponsored by BJP or by Shiv Sena, the main Hindu fundamentalist parties, are especial favourites. Watching Patwardhan’s films entails an education in watching the ways that crowds watch politicians perform and listen to performers politicise.

Perhaps Patwardhan’s most consistent cinematic signature is the song. Whether it is the harvest song that concludes A Time to Rise 1981 or the Internationale that is sung in Punjabi in In Memory of Friends or the song sung by Vilas Ghoghre, the charismatic Dalit bard, that guides the listener through the travails of poverty in Bombay: Our City 1985 or the anti-caste song We are not your Monkeys, that Patwardhan co-wrote with Dalit poets to critique the Hindu epic Ramayana, the song conjures powers of gathering and solidarity, memory and futurity that play an important role in the montage and the mood of the Patwardhan film.

Jai Bhim Comrade, indeed is propelled and narrated through songs. It is a documentary in the form of a musical that reflects upon cinema’s power to commemorate the mnemonic power of song. In its narration of endangered histories and its call to the future of the Dalit movement, Jai Bhim Comrade offers viewers the opportunity to review all Patwardhan’s films, to revisit his signatures and to receive his preoccupations again, as if for the first time.

Each film in A Cinema of Songs and People: The Films of Anand Patwardhan will be introduced by Anand Patwardhan, Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun, followed by audience discussion after the screening. Guest speakers include filmmaker John Akomfrah, critic TJ Demos, artist and critic Janna Graham, political campaigner Kate Hudson, journalist and writer Salil Tripathi, psychiatrist & medical anthropologist Sushrut Jadhav, and political historian Shirin Rai.

Curated by The Otolith Collective