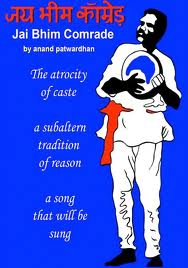

JAI BHIM, COMRADE PATWARDHAN

21/03/2012 SUNALINI KUMAR

How many murdered Dalits does it take to wake up a nation? Ten? A thousand? A hundred thousand? We’re still counting, as Anand Patwardhan shows in his path-breaking film Jai Bhim Comrade (2011). Not only are we counting, but we’re counting cynically, calculating, dissembling, worried that we may accidentally dole out more than ‘they’ deserve. So we calibrate our sympathy, our policies and our justice mechanisms just so. So that the upper caste killers of Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange’s family get life imprisonment for parading Priyanka Bhotmange naked before killing her, her brother and other members of the family in Khairlanji village in Maharashtra, but the court finds no evidence that this may be a crime of hatred – a ‘caste atrocity’ as it is termed in India. Patwardhan’s film documents the twisted tale of Khairlanji briefly before moving to a Maratha rally in Mumbai, where pumped-up youths, high on testosterone and the bloody miracle of their upper caste birth are dancing on the streets, brandishing cardboard swords and demanding job reservations (the film effectively demolishes the myth that caste consciousness and caste mobilisation are only practised by the so-called ‘lower castes’). Asked on camera about the Khairlanji murders, one Maratha manoos suspends his cheering to offer an explanation. That girl’s character was so loose, he says, that the entire village decided to teach her a lesson.

How many murdered Dalits does it take to wake up a nation? Ten? A thousand? A hundred thousand? We’re still counting, as Anand Patwardhan shows in his path-breaking film Jai Bhim Comrade (2011). Not only are we counting, but we’re counting cynically, calculating, dissembling, worried that we may accidentally dole out more than ‘they’ deserve. So we calibrate our sympathy, our policies and our justice mechanisms just so. So that the upper caste killers of Bhaiyyalal Bhotmange’s family get life imprisonment for parading Priyanka Bhotmange naked before killing her, her brother and other members of the family in Khairlanji village in Maharashtra, but the court finds no evidence that this may be a crime of hatred – a ‘caste atrocity’ as it is termed in India. Patwardhan’s film documents the twisted tale of Khairlanji briefly before moving to a Maratha rally in Mumbai, where pumped-up youths, high on testosterone and the bloody miracle of their upper caste birth are dancing on the streets, brandishing cardboard swords and demanding job reservations (the film effectively demolishes the myth that caste consciousness and caste mobilisation are only practised by the so-called ‘lower castes’). Asked on camera about the Khairlanji murders, one Maratha manoos suspends his cheering to offer an explanation. That girl’s character was so loose, he says, that the entire village decided to teach her a lesson.

Hmm. Perhaps, after being raped, paraded naked and killed, she will re-evaluate her choices, in particular of being Dalit and female? Caste has always offered a lovely way out of the ethics of taking life in India – as an upper caste (male) person, you are given a package deal – express your loathing of the lower orders, get a little sexual excitement if the victim is female, AND re-establish the rule of dharma in the community. Which right-thinking savarna man wouldn’t jump at this offer? And so the hate crimes continue in their depressing uniformity. One has to wonder what imagination of morality must put the adrenalin into the limbs of men who are able, at the right moment, to know exactly what to do, which limbs to hack, which clothes to tear off and how to celebrate afterwards. To express through their bodies and words a hatred that can only be satiated by the utter dehumanisation of their victims and of themselves. Weeks and months after the crime, perhaps decades later as old men, do they sit in their armchairs and feel a twinge?

We will never know. In the meanwhile, Patwardhan offers us this labour of love, this labour of anguish, shot and edited over fourteen years in a city he calls home, Mumbai. Starting with the suicide of a friend – the gifted Dalit poet-singer Vilas Ghogre – Patwardhan delves into the making of what I have called elsewhere ‘one tragic statistic’. Patwardhan discovers that Ghogre hanged himself from the ceiling of his tiny hut a few days after visiting Ramabai Colony – a predominantly Dalit slum in Mumbai that had just lost eleven of its residents (including a boy) in police firing. That was the last straw for Ghogre – a poet and singer, humiliated by lifelong poverty and having been expelled from the Communist party for ‘deviations’ from the path, Ghogre decided, as his friend and comrade puts it in the film, that “this country was not worth living in.” Jai Bhim Comrade is about Ghogre’s death and Bhai Sangare’s death and other Dalit deaths; it is primarily about connections that we prefer not to make, a million synapses and nerve-endings that even the most sensitive of us must cauterise to live our alienated lives in “this country”. This country, which treats 165 million of its population as if they deserved to clean our shit and unblock our sewers, lie low, remain invisible, not dare to form a party, unionise or God forbid, observe their dirty festivals in our public space. Including Ambedkar Jayanti, a joyous annual celebration of the life and teaching of the only national leader, Patwardhan reminds us, whose popularity continues to grow long after his death. A leader whose prediction that without a social revolution, the political revolution of independence would become meaningless has been coming true for the past six-odd decades. But Jai Bhim Comrade is not a depressing film – it is a profoundly layered meditation, a sombre one, certainly, on the matrix of power and blindness that buttresses our society. It is a provocative, sometimes angry tribute to a lost hope – the hope that the Left movement and the Dalit movement in this country could speak to each other, a hope that flickered in the seventies and eighties with the formation of the Dalit Panthers but was swallowed either in bitter feuds or in mind-numbing discussions of the party line on ‘The Caste Question’. Above all else, Jai Bhim Comrade is a film about music and poetry – the music and poetry of those who often have little else. Bursting out of loudspeakers and drums and one-stringed instruments, riding on the beautiful young voice of Sheetal Sathe of the Kabir Kala Manch, soaring over rooftops and narrow streets in shanties and slums, spurring on an ancient Dalit woman to dance at a midnight concert, this music cannot be contained. Hopefully, the revolution can’t be, either. Jai Bhim Comrade.

Read more reviews of the film here, and here; and if it is being screened near you, please make time to watch it.