Freedom of Expression and the Politics of Art

The Hindustan Times, 2004

Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali was panned at home for purveying “negative” images of Indian poverty. It went on to win acclaim at Cannes and the rest is history. One could hope the same happy denouement would unfold for Rakesh Sharma’s Final Solution which was unceremoniously rejected (read censored) by the selection committee of the Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF) for Documentaries, Shorts and Animation Films, only to win two prestigious awards at the Berlin International Film Festival.

But the hope would be belied. What happens to the cinema after all is not divorced from what happens to society as a whole. Today the moral police is out on the prowl looking for the “enemy within”. Some wield the big stick of the State and others the narrow-minded, self-righteousness of the super “patriot”. Some dictate from the corridors of power what is right and wrong, what is “culture” and what is obscenity, what is “Indian” and what is “Western”, what is history and what is myth. Others whose buying power allows them only the tiniest crumbs of the promised consumer cornucopia are empowered by a State that looks the other way when the faithful begin to riot and loot. They form themselves into mobs that destroy paintings, threaten artists, tear down museums, shred ancient manuscripts, all in the name of God and the holy Motherland.

So for political documentaries that take on the State and religious fundamentalists, there is little hope of official sanction and recognition. Indeed whatever space these films wrest for themselves must be jealously guarded and cautiously expanded. Why speak only of art? Everywhere the democratic space is shrinking. As election after blood-soaked, manipulated and corrupted election brings the far-right ever closer to total control, we have to wake up and rouse ourselves to stand up and be counted in defence of our Constitution and our right to live as a humane people. As Constitutions go, ours must rank as one of the best. It came as a culmination of the freedom struggle, it was drafted by a team led by Dr. Ambedkar, one of the greatest thinkers and leaders of our time and a champion of the most oppressed sections of our society and it enshrines the values of a secular democracy that has egalitarianism as a core ideal. In it the Right to Freedom of Expression is guaranteed as a fundamental right. Small wonder then that the ruling ideology of India today as openly stated its intention to amend the Constitution once it has sufficient numbers to do it.

It is in this larger context that recent events must be viewed. Last year faced with the fact that many Indian documentary films that questioned the socio-political policies of the State and criticized the rising tide of religious hatred had won prizes and attracted world-wide attention, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting took the extra-ordinary measure of imposing a new rule that demanded that all Indian films be censored prior to entry into MIFF 2004 while foreign films remained exempt.

Documentary filmmakers across the country were galvanized into action. Over 275 filmmakers exchanged ideas and action plans, formed a Campaign Against Censorship at MIFF and threatened to boycott MIFF altogether if the censor certificate requirement was not removed. As a result of a united and popular campaign, the rules for MIFF were amended and the censorship clause withdrawn.

There nevertheless was an apprehension that there would be an attempt to introduce censorship through the backdoor – ie – by eliminating “uncomfortable” films from the festival through a manipulated selection process. These fears came true. MIFF 2004 rejected some thirty of the most outstanding new Indian films made on a range of themes – primarily political. Amongst the reject films was Rakesh Sharma’s meticulously documented and searing Final Solution on State complicity in the Gujarat massacres and Shubhradeep Chakravarty’s Godhra Tak a film that questioned the official version of how the fire began that burned 59 Hindus to death and led to the large scale revenge killings of Muslims. Also rejected was Sanjay Kak’s Words on Water a film that documents the immense courage of the Narmada Bachao Andolan that fights for those displaced by gigantic dams on the river Narmada – dams that history will surely judge and remember as monuments to man’s greed and folly. Amar Kanwar’s Night of Prophesy a moving tribute to the protest culture of the marginalized met the same fate. The censor’s unofficial axe did not fall only on the most hard-hitting of political films. Also rejected were more personal and reflective films like Vasudha Joshi’s Girl Song, positive and constructive films like Anjali and Jayashankar’s Naata and observational films like Pankaj Rishi Kumar’s Mat. These films must have paid the price for the fact that despite a softer tone, their critique of the rising tide of religious fundamentalism remains unmistakable. Communalism was not the only issue the censors found to be unpalatable. Sex workers who speak up for themselves without apology (Shohini Ghosh’s Tales of the Night Fairies, Bisakha Dutta’s In the Flesh ) met the same fate. The reason for excluding Rahul Roy’s City Beautiful a film that painstakingly observes the deteriorating conditions of two working class families in New Delhi was perhaps best revealed in the statement of one of the selection committee members: “Why should we show films that tarnish the image of India?”

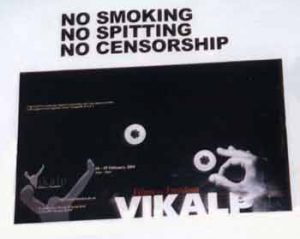

We decided that the best way to fight censorship was to screen the “rejected” films at a venue near MIFF so that the public could decide for themselves. By this time 14 filmmakers whose films had been selected by MIFF decided to withdraw from MIFF in protest against censorship. The films that were withdrawn from MIFF joined the screening list and a new festival VIKALP: Films for Freedom was born. Each filmmaker pooled in Rs 1000, two friends put in Rs.10,000 each and with this shoestring budget, armed with Mini DV tapes and a video projector we went in search of an appropriate hall near the MIFF venue. We found the perfect one. Bhupesh Gupta Bhavan houses the printing press of the Communist Party of India. Their solidarity was unconditional and total. They did not ask for a penny for the hall and all our printing became free once they realized that we really had no budget. Of course their large hall posed a problem as it had terrible acoustics and a low ceiling. We put thick curtains on the windows, did away with chairs, put mattresses on the floor and a shoe rack outside the hall. Volunteers poured in from all over the city and some arrived from across the country. Almost overnight, as if by miracle, a full fledged, beautifully running peoples film festival was underway.

Publicity for VIKALP was by word of mouth but incredibly, we had a full house from day one and people had to be turned away The festival opened with an excerpt from Sadaat Hasan Manto’s Safed Jhoot, an indictment of censorship and hypocrisy, performed by Jamil Khan, directed by Naseeruddin Shah and introduced by Ratna Pathak Shah. The electricity generated by the play was palpable and it did not get diminished for a moment throughout the day as exciting films and discussions followed each other without pause till nightfall.

Spokespersons at MIFF, like their counterparts in the Central Board of Film Certification (the Censor Board) have always done, continued to deny that any political censorship had occurred and claimed that all films had been rejected on merit alone. Notions of “art” are often brought in to defend existing ideologies. It is instructive to note that the filmmaker that MIFF chose to honour this year was Leni Riefenstahl, the creator of Hiltler’s best known propaganda films. MIFF opened their festival with her salute to Nazi supremacy The Triumph of the Will (1936). At the same time MIFF rejected Rakesh Sharma’s Final Solution a film whose subject matter and title is a clear warning that fascist ideas are rampant in our country and history has begun to repeat itself.

Selection committees and juries may not realize the choices they have made. People inevitably bring their world-view and their politics to the table, sometimes disguised from their colleagues and sometimes even from themselves, disguised all too often, as notions of “art”.

Anand Patwardhan