Portraits of India:

interview with Anand Patwardhan

With a weekend of films at BFI Southbank providing a rare opportunity to catch up with the work of one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary documentary cinema, writer Georgia Korossi spoke with Anand Patwardhan about his impassioned portraits of India.

By Georgia Korossi

21 February 2013

BFI Southbank’s tribute to leading Indian documentary-maker Anand Patwardhan is exciting news: it’s a rare opportunity to find the film medium engaging with the experiences of ordinary people, and is bound to prove a rich source of inspiration for new filmmakers.

Regrettably, I only discovered Patwardhan’s work very recently but I was instantly drawn to his clear-minded approach and his impassioned argument for a just society. His landscapes of India, seen through his camera since the 1970s, are integrally connected to an activism for communal harmony. Yet controversial issues betray India’s primary principles of non-violence, secularism and egalitarianism and people experience what looks like an unchanging reality.

Regrettably, I only discovered Patwardhan’s work very recently but I was instantly drawn to his clear-minded approach and his impassioned argument for a just society. His landscapes of India, seen through his camera since the 1970s, are integrally connected to an activism for communal harmony. Yet controversial issues betray India’s primary principles of non-violence, secularism and egalitarianism and people experience what looks like an unchanging reality.

While his films are not planned out in advance, Patwardhan became a cameraperson out of necessity, which encourages directness with the people he talks to and an appreciation of their viewpoint. He does both the camerawork and the editing, and the breathing space he leaves between shots of controversial material allows viewers time to gather their own thoughts.

Like Patricio Guzmán and Fernando Solanas, Anand Patwardhan engaged with the political logic of Julio García Espinosa’s 1969 manifesto ‘For an imperfect cinema’. Espinosa stated, “Imperfect cinema can enjoy itself despite everything that conspires to negate enjoyment.” Patwardhan’s work is under constant threat of censorship by television networks and governmental authorities in his country. Nonetheless he has fought and found alternative distribution methods for his work.

His films make no assumptions, and have no formulaic thinking. Instead, they subscribe to the moral implications of tragic international human actions interwoven with songs that awaken the listener. Simply put, State of the Nation is one of the year’s essential film seasons – Patwardhan’s films should be seen by everyone, from fishermen to school children.

I often find that watching your films is like reading a book. War and Peace (2002), for instance, is divided into six chapters and an epilogue binding together questions of nationalism, Hiroshima, science and war as profit against the law of love and education. This type of film is often called a film essay. Is this approach intentional to allow a comprehensive understanding of the seriousness of worldwide matters?

I am not much of a cine theorist and was unaware that the form I ended up with is being described as an essay. I remember being irritated when my films were branded in some circles as ‘agitprop’ so although I don’t find labels too useful, ‘essay’ is definitely a better one. My problem with the ‘agitprop’ tag is not that I disavow the engaged nature of filmic intervention, but that the word ‘prop’ is short for ‘propaganda’ and propaganda is generally what one does not agree with or trust. At best the label reeks of a subtle put-down from those who believe that art and politics are mutually exclusive and there is a pecking order between them. In this sense the term ‘essay’ is free from prejudice, unless one detects in it the subtle hierarchy between prose (the domain of the direct communicator) and poetry (the realm of the artist).

I will grant that my films are perhaps somewhat more verbal than visual in that I am wary not to rob people of their voice and steal only their image. I want my films to be cross-pollinators, carrying voices across natural and man-made divides. In deeply unjust and segregated societies they do the job of democracy. Silence or non-verbal moments in these films occur rarely, but when they do, they are significant precisely because they are rare.

There are chapters in War and Peace but these chapters, or this structure, did not emerge from anything pre-formulated at the research stage but from material gathered over the four years the film took. It was while trying to make sense of diverse sequences that I had boiled down on the edit table, because they felt important, that I eventually found a means of stringing them into a narrative that began to make sense.

There are chapters in War and Peace but these chapters, or this structure, did not emerge from anything pre-formulated at the research stage but from material gathered over the four years the film took. It was while trying to make sense of diverse sequences that I had boiled down on the edit table, because they felt important, that I eventually found a means of stringing them into a narrative that began to make sense.

In recent years, documentary filmmaking has received a wider appreciation. Perhaps due to a number of documentary film festivals, more people have the opportunity to practice this medium. But can it change the world?

People like us obviously believe our films can change at least some tiny part of the world or else we would have lost motivation a long time ago, because our work is neither the irrepressible product of self-expression nor meant for the collector’s cupboard. I remember seeing Patricio Guzman’s The Battle of Chile (1975-79) in the 70s and it made a huge impact on me as it did on so many. But Pinochet ruled into old age while many of those he murdered remain unsung. The magic of the Allende years never returned and yet the memory and the inspiration of those years are forever captured on film.

Similarly, I cannot honestly claim that my films made a significant difference to the political realities they describe, but feel confident that those who were exposed to them were in some small way marked. I also believe that if the gatekeepers of the state and the marketplace (who increasingly control what gets seen and by whom) did not succeed so well, our films would indeed have made a far greater impact than they have done.

As for documentary festivals, in earlier years they played a vital role in popularising the medium and showcasing work which would otherwise have remained isolated, but today genuinely independent documentary cinema no longer has a natural home. The reason is the commercialisation of the documentary.

Most major festivals have turned into pitching zones where in five minutes flat, commissioning editors do thumbs up or thumbs down to competing performing monkeys. Once selected these mostly white folk are sent into the jungles of the world to come back with a quickie that will run for 52 minutes and tell people what they already know, because anything more would be too taxing and would risk the channel being switched.

We live in times of insecurity as more and more people lose their jobs, almost one in seven people in the world lives in poverty, and yet the promotion of nuclear weapons continues. Many people find this reality hard to grasp and this, I feel, is part of the argument in War and Peace. Can you explain how you started this project?

War and Peace is in part an answer to those who believe that national ‘security’ depends on acquiring ever-greater military might. In a country like India this is patently ludicrous. What does a starving farmer care whether we massacre millions of Pakistanis or Chinese with our atom bombs before or after they massacre millions of us? Nuclear nationalism is the game of powerful elites, although through widespread propaganda they do evoke jingoism in the wider populace. At the best of times, even without the nuclear element, nationalism serves the interests of a tiny class when it is divorced from principles of justice.

My horror at militarisation and its escalation to the nuclear is not restricted to countries like India and Pakistan on the grounds that we can ill afford it. The horror is even greater when a country from the first world like the USA spends zillions on weapons of mass destruction and supplies the rest of the world with its military arsenal because they are so scared that they cannot hold on to economic superiority forever without overwhelming military might.

I’m quoting Sheema Kermani, the Pakistani dancer in War and Peace who performs while Gandhi’s favourite hymn plays in the background: ‘When one is touched people can transform themselves.’ Can you explain the importance of this?

Not only was she braving fundamentalists by adopting a dance form that originated in pre-Partition India, but through this hymn she invokes: “God or Allah be your name, grant wisdom to us all”. As she says, it is precisely because dance (and music) can touch people’s hearts and transform them that the fundamentalists want to ban it.

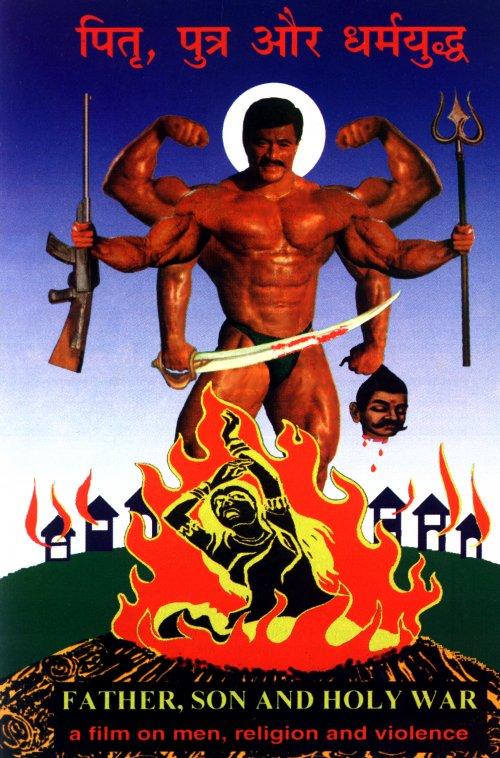

The end credits of your film Father, Son and Holy War gratefully acknowledge the Black Audio Film Collective. How did you first hear about the Collective’s work and how has it influenced yours?

The end credits of your film Father, Son and Holy War gratefully acknowledge the Black Audio Film Collective. How did you first hear about the Collective’s work and how has it influenced yours?

I first met the Black Audio Film Collective (now renamed Smoking Dogs Films) in the early 80s when I showed my films while passing through the UK and we have kept in touch since, more as personal friends than as official collaborators. Whenever I needed help they were always there.

John Akomfrah and Ilona Halberstadt were also the first in the UKto do an article and interview on my work for Ilona’s PIXmagazine. This was international solidarity. Even now, many of my 16mm prints take up valuable space in the Smoking Dogs loft as the BFI National Archive turned me down when their mandate to preserve non-British made films shrunk in the face of cutbacks.

London in the 80s and 90s was always a source of sustenance for me, though I never spent more than a few days at a time there. A major inspiration was John La Rose and all the people associated with the Black Bookfair. It was here that I briefly met the amazing Linton Kwesi Johnson after having admired his work from afar. So I am quite thrilled that he agreed to talk with me on stage after the screening of Jai Bhim Comrade (2012) at the BFI this week. Casteism in India and racism in the west are two sides of the same coin and fighting this through music and poetry is what connects Linton to the people in my film.

What’s your message to future documentary filmmakers?

No message really. Do it only if it burns when you don’t.

World-renowned reggae poet and recording artist Linton Kwesi Johnson chaired a conversation with Anand Patwardhan in February 2013, following the screening of Patwardhan’s Jai Bhim Comrade at the NFT1.

The programme State of a Nation: Anand Patwardhan’s Portraits of India ran at the BFI Southbank from 23-25 February 2013.