‘All of My Work Is Endangered’:

Anand Patwardhan on the Future of

Documentary Films in India

Mark Rappolt | 22 October 2021 | ArtReview Asia

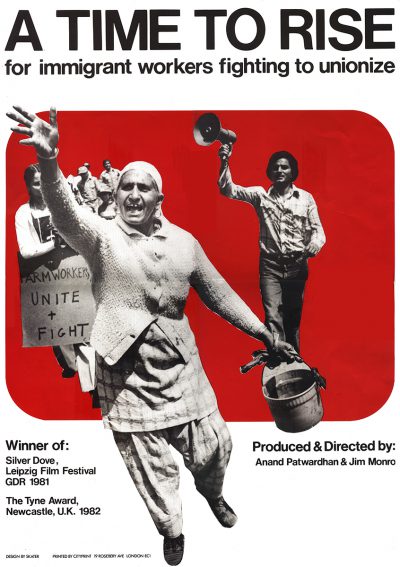

Born in Mumbai, Anand Patwardhan is one of India’s leading documentary filmmakers. Over his five-decade-long career he has produced 17 feature-length films and numerous shorter works that broadly tackle issues of social and political injustice, the rise of nationalism and religious fundamentalism, and the iniquities of India’s caste system. While his work has been praised internationally – in the form of awards and festival appearances, as well screenings in art institutions such as MoMA and Tate Modern, and the inclusion of his work in visual art festivals such as Documenta 13 and the 2014 Gwangju Biennale – Patwardhan has spent much of his life fighting its censorship in the land of his birth. Bombay: Our City (1985) was only broadcast after a four-year court case, while Father, Son, and Holy War (1995) was screened on India’s national television network in 2006 after a decade-long legal battle and a Supreme Court order that it should be shown without cuts. War and Peace (2002) was originally refused certification unless a total of 21 cuts were made and was banned for a year while the director took the Indian government to court, eventually winning the right to screen it with no cuts at all. Among numerous other awards, it eventually won the National Film Award for Best Non-Feature Film in 2004. His first film, Kraanti Ki Tarangein/ Waves of Revolution (1974), documented the movement and protests against corruption and state oppression in the Indian state of Bihar. His most recent film, Vivek/Reason (2018), a four-hour investigation into the dismantling of India’s secular democracy and the violence that comes with it, has yet to receive a theatrical screening in India (a Hindi version has made its way to YouTube, and it was part of a full retrospective of Patwardhan’s films that screened on the documentary platform OVID.tv earlier this year). The seventy-one-year- old talked to ArtReview Asia from his home in Mumbai about what keeps him going, his latest campaign against censorship, his hopes for the future of documentary filmmaking and why he doesn’t consider himself an artist.

ArtReview Asia Over the last month or so you’ve been campaigning against the Cinematograph (Draft) Amendment bill?

Anand Patwardhan Yes, but not enough people are speaking out. Many mainstream filmmakers who make big-budget films don’t want to take risks, so toe the line no matter what happens. As you know, by law, every film produced in the country has first to be certified as being publicly viewable by the Central Board of Film Certification [CBFC]. I have fought and won many legal battles against the CBFC in the past, and in the end my films were certified without any cuts. The new proposed bill is crazy – it allows the present rightwing government to remove clearances that were granted under previous governments. All of my work is endangered. Clearly this kind of law, while it pretends to protect ‘public morality’ and ‘sensibility’, is aimed at the human-rights- oriented films we made, films which somehow got through the system in the past, some bruised and some intact.

ARA Is that symptomatic of a more general contraction in the scope for free speech in India at the moment?

AP There is little free speech now in India. Here and there people do speak out and the government cracks down and there are different levels of crackdown. People have been murdered, sometimes jailed, sometimes their work is prevented from reaching the public. Generally, the ways of reaching audiences are shrinking: both because of government actions but also due to the pandemic. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, I haven’t done any big public screenings. We’re now doing them on the internet, where you get a few hundred or at best a few thousand views at a time.

ARA I guess an online audience is a different kind of audience.

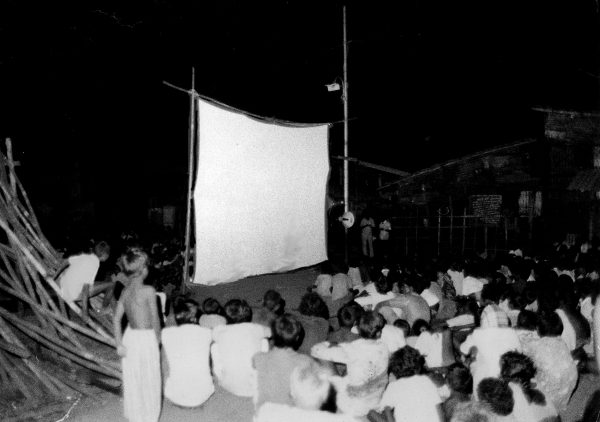

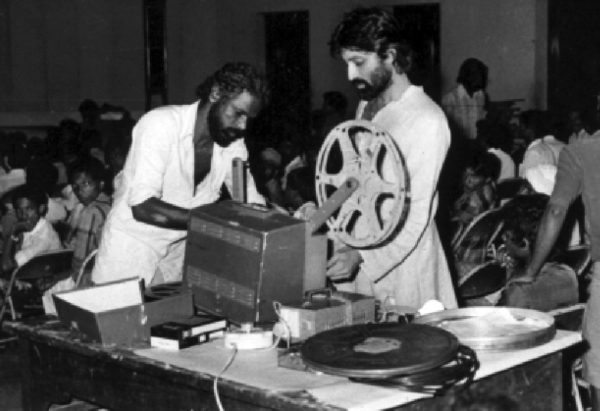

AP It’s people who can afford computers, who have electricity and all of that. It’s people watching one screen, usually alone and having no discussion with others. Half the fun of films like mine is the discussion after the screening. I’ve been doing this ever since I started making films on celluloid, before the digital age. We carried large 16mm projectors and screens and held discussions after. The advent of lighter video projectors made things easier – we did lots of screenings in working-class neighbourhoods, hoisting huge, sewn-up bedsheet screens on bamboo frames dug into the earth.

ARA Is the topic of discussion and debate and how you can engender that something you’re already thinking about when you are making the films?

AP I’m not consciously thinking about how people will respond to the films. I don’t want to oversimplify things so people will get what I’m saying. Perhaps I don’t worry about that because I’m not a super intellectual in the sense that I never use extreme theoretical language in my films anyway. Anyone with common sense can follow them. I make films assuming that audiences have at least the same intelligence as me. My experience with working-class audiences and even with the fairly young is that our films are very accessible. The discussions that follow have been an important learning experience for me. I don’t reduce complexity, but I do make different language versions for different regions of India.

ARA What inspires you to embark on a film project?

AP I’m never impatient to jump into making my next film. The process of screening films already made takes years. So there are often long gaps in between filmmaking. It’s not that I think about a project, write a proposal and wait for funding. Events in real life trigger a film.

It’s only when I get pretty upset that I actually end up making the film, when I can’t avoid it anymore. I often don’t know that I’m actually making a film until I’m well into it. I have my own equipment and often shoot things of interest over a period of time. If that interest is sustained, slowly a film emerges from it.

At other times no final film gets made and the footage remains as an archive, or bits and pieces get posted on YouTube or Facebook as a talking-point quickie.

ARA What makes you upset?

AP The last film I made before Reason [2018] was a film called Jai Bhim Comrade [2011], a three-hour-plus film that took me 14 years to make. It was triggered by the suicide of a poet-musician Vilas Ghogre, who was a Dalit. Dalit literally means ‘the oppressed’. Historically Dalits were treated as ‘untouchables’ and are often still treated as such. Their greatest contemporary leader was Dr B. R. Ambedkar [1891–1956], who broke barriers against education to win doctorates from Columbia University and the London School of Economics before returning to India to fight for an egalitarian society. Dr. Ambedkar led the team that drafted India’s Constitution and became Independent India’s first Law Minister. Shortly before he passed away, in 1956, he, along with thousands of his followers, walked out of the Hindu religion that had enforced an oppressive caste system, to embrace Buddhism, a religion that did not believe in a caste.

Vilas Ghogre was inspired by Dr. Ambedkar but had also become a Marxist. His song Who’s city is this? runs through my film on the homeless, Bombay: Our City [1985]. Twelve years later, in the Dalit colony of Ramabai Nagar, someone in the middle of the night placed a garland of footwear on their statue of Dr. Ambedkar. When the residents of the colony woke up, they found their statue desecrated and came out on the street to protest. Within half an hour police arrived and shot into the demonstrators and into the colony, killing ten people on the spot.

Vilas, who lived not far away, visited the colony and got so depressed that he hanged himself in his tiny room. On a board in the room he had written in chalk, ‘Long live Revolution’ and ‘Long live Ambedkarite unity’. Vilas was an Ambedkarite who had become a Marxist, yet before he died, he wore a blue bandana on his head (blue is the Ambedkarite colour) to reassert his Dalit identity rather than his Marxist identity. Jai Bhim Comrade, which began as a homage to Vilas, became an exploration of class and caste and how these interplay with each other, at times converging and at times diverging.

I used to help produce audiocassettes by recording Vilas’s songs, which his group would then sell, so I had many of his songs on tape but had visuals of him singing just the one song filmed for Bombay: Our City. So I started filming other living poet-musicians who followed his tradition, and that’s where Jai Bhim Comrade [JBC] led me. Of course the film also followed court cases that began after the Ramabai killings, both against the police, and the police’s counter-cases against the people they had shot at.

The trigger point for a film might be one thing, but a film doesn’t necessarily stay there, it takes off from there. The film that I made before JBC was War and Peace [2002], which was triggered by the nuclear tests that India performed [in 1998], and then Pakistan did a few weeks later. For that I ended up filming for over four years in India, Pakistan, Japan and America. I was already shooting JBC from 1997 on, so the making of War and Peace overlapped till the latter got completed in 2002. Neither film had an official ‘budget’ and both were made with rudimentary equipment.

More generally, over the last few decades I’ve made films about different aspects of religious fundamentalism. Especially the rise of Hindu fundamentalism. I was born a Hindu, and Hindus are the majority community in India who are increasingly being socialised into paranoia about a relatively tiny Muslim minority. Being from the majority community, I feel a sense of responsibility.

ARA And a sense of guilt?

AP It’s a feeling of anguish really. It’s so stupid that an over 80 percent majority starts to believe they’re insecure because they are brain- washed into fearing a 14 percent minority. I’m referring to Muslims here, but there is a bigger elephant in the room, which is the caste system that has oppressed Dalits and other ‘lower’ castes for thousands of years. Here I do have a feeling of guilt, because I belong to the so-called upper caste. I’m part of a privileged community that has benefited from the caste system. Benefited materially, yes, but intellectually the false pride of caste impoverishes all those who refuse to question their own privilege.

ARA You work in the genre of documentary and I think that the common-sense definition of that would be that it has a stronger relationship to truth than a work of fiction.

AP Mostly, yes, though there can be truthful fiction as there can be documentaries that promote falsehood. But at least the kind of documentaries I make don’t invent what is in front of the camera. I have very rarely reenacted events, and whenever I did, I signalled this as reenaction and not as documentary footage. With documentary, my creativity comes in the editing process and not so much in the filming process. My films usually take a long time to make. I shoot something, look at it for a long time and then know what else I need to shoot

to complement that. The editing process also helps the filming process because it leads me in a direction. I’m not really self-conscious about my process. When we’ve gone out on a shoot and I come back home and start editing, I reduce my materials so that I don’t have to watch hundreds of hours. I reduce the material shot for that day or the last few days into a sequence, leaving out the stuff that’s not usable and keeping whatever I think may conceivably be useful. So I have lots of little pieces of the film that emerge over a period of time, and it’s like a jigsaw puzzle, which later on falls into place. I make the story much later, not at the beginning. When I’ve actually got a body of material, which I think is saying something, then I start to break it down into its elements and then juggle them around to see how best the story can be told. The narrative part of it, the parts where you hear me or a narrator speaking or have intertitles doing the same job, are actually the moments where I wasn’t able to make the material speak for itself.

ARA So would the perfect film then have no voiceover?

AP Yes, probably. I have made some films without any voiceover at all. Bombay: Our City is one of them, but there are several where I didn’t need to say anything. The material spoke for itself and all I needed to do was to organise it, but there are also films which have historical content, which I can’t film and so there’s archival material, narration, animation, etc, to make the linkages.

ARA Do you believe in an absolute truth?

AP No, there’s never an absolute truth. By definition, everything is subjective, so the idea that I’m telling the truth is just my truth. Anybody who looks at a situation will tell their truth. They have to be true to themselves and that’s the only thing you can do, because you are by definition subjective.

ARA Ideas of democracy have been present in most of your work. Is that something you feel increasingly pessimistic about in relation to India?

AP It’s a cyclical process. Basically, I think that we’re obviously at a very low downturn, probably the darkest period since Independence, but it’s not going to stay that way, that is clear. You can already see things that are happening that are going to overturn the system as it is right now. I’m hoping that people will soon reach the end of their tolerance for rising fascism.

ARA Your films don’t shy away from tackling difficult situations, but do you think you are optimistic in the sense you just mentioned?

AP I’m always optimistic. Not as a political choice, but because it’s a form of survival. If you’re not optimistic, then you commit suicide, either physically or mentally.

ARA Are you optimistic of the future, then, of documentary cinema, given the obstacles that seem to be placed in your way?

AP I think that while there are many great films made, I’m very perturbed by the way in which films are produced. I’ve been to so many film festivals, international film festivals that are very famous, which concentrate on marketing, concentrate on selling. The Sheffield International Documentary Festival [where Patwardhan won the Inspiration Award in 2013], for instance, even calls its most popular section ‘The Meet Market’ (pun obviously intended), where all the commissioning editors, sales agents and filmmakers gather. Amsterdam and other famous docufestivals do the same.

Almost all festivals have this major focus on selling and buying, and so you have commissioning editors from a few Western, well-off countries that gather together in a small group, and then they basically vet the possible subjects and ways of filmmaking. Filmmakers play the game because the only way they can raise money is to prepare a five-minute piece that will attract the commissioning editor.

What ends up happening is that people get what they already know. The presumed consumer is an outsider, completely separated from the subjects of the films. I’m talking now mainly about films from India, or Africa, or films from any countries that were once described as ‘Third World’. They’re being made for and consumed by first-world countries because that’s where the money is.

The first-world countries determine what you’re going to say and how you’re going to say it. In the old days – I’m talking about 25, 30 years ago – when the system – the buying and selling – was not fully in place, there was emphasis on the individual film that got made by hook or by crook. The filmmakers somehow managed to produce a film, out of a grassroots need for that film to be made, and then the film got noticed and travelled around the world. But now it rarely happens that way. It happens in reverse. It happens that films first get commissioned, then get made.

ARA When you talk about grassroots needs, are you talking about the needs from the point of view of an audience or for the truth that should be told?

AP I’m talking about the need for certain issues to be highlighted and shown to the world in a language accessible to the subjects of the film. You don’t necessarily see in the world the films that are the most important to see. You see the films that are the best marketed.

ARA So what makes an important film?

AP Films that promote democracy and egalitarianism or fight hatred and climate change are just a few examples. I’m not saying these films are not being made, but they’re being made not organically but in a mechanical, preconceived way. The gatekeepers think that anything else is too difficult for their audiences and they decide what their audiences want.

My kind of filmmaking actually falls on its face, because I don’t work that way. My films cannot be easily slotted, because, for one, they don’t adhere to a fixed timeframe and formula.

My last film was four hours long. It’s almost impossible to sell it to any television company in the world. Where it could have been easily slotted would have been places like Netflix and Amazon, who could easily have serialised it. But they’re afraid of the content. Afraid of being thrown out of India. It’s a lucrative market and anything strongly critical of the government or its ideology will cause them trouble.

Even Mira Nair’s film A Suitable Boy [2020, a BBC TV production] got into trouble because it showed a romance between a Hindu and a Muslim. Netflix didn’t take it off, but there was a lot of noise made by the rightwing. Since then, apart from the new Cinematograph Act Amendment, the government also wants to control Ott platforms by saying that if enough people complain about a film, then the government can recall the permit to show the film. All they have to do is to mobilise a few RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, an extreme Hindu nationalist organisation] people to write in complaints. Even YouTube, Facebook and Twitter have been made to play dog.

ARA In some ways, you’re part of a network of activists who have been working for a long time in India to address issues that lie at the heart of the country’s societal divisions. And your filmmaking is suggestive of this activist approach in the sense that you turn up to a protest or you turn up to a meeting and record it. Without, as is often the case in films that are shown in the context of the artworld, it having been commissioned by a foundation or a museum, or being marketed for sale by a commercial art gallery. Yet your films have been shown in art festivals like the Gwangju Biennale [2014] and Documenta 13 [2012] and attract the interest of numerous curators in art institutions. Do you think these are two separate worlds?

AP I don’t know much about the artworld. And I prefer the word citizen to the word activist. While sometimes I shoot in places where I already know the people well, at other times I haven’t spent a lot of time doing research with the community before I start filming. I often make friends as I go along. Get to know people, shoot over a period of time, that’s one way. In the case of Bombay: Our City we were trying to stop the demolition campaign that the city had launched against the homeless. For legal purposes, I was taking pictures for a lawyers group that was fighting the demolitions. Eventually, I started shooting on film, and then that became Bombay: Our City. There’s often a kind of activism that has begun before the film began. Even with the very first film that I made, Kraanti Ki Tarangein/Waves of Revolution, in 1974 [which documents the protests, marches and meetings related to the Bihar movement against corruption and state oppression, and is dedicated to ‘the revolutionary people of India’], I wasn’t there to make a film. I was there without a camera, but then on a particular day, when a demonstration was planned, the people in the movement said I should take photographs to record the police violence. In the end I borrowed a Super-8 camera from a friend and then projected it onto a screen and refilmed this with a 16mm camera borrowed from a friend.

ARA What makes an artist?

AP I think that is important to discuss. What is art? Is an artist an artist because the artist says he or she is an artist? How do you decide that something is art and something is documentary and something is propaganda and something is agitprop? All those labels have been thrown. For me, art is something that the artist does not decide. Art is something that is decided by posterity, art is something that happens because, over a long period of time, it remains relevant or gains in value. Something communicates across language, across geographies, across time.

I’ve never called myself an artist because I don’t think anybody has the right to do that. For me, art is a byproduct of the work that you’re doing and it’s not something that you can self-consciously create. Art happens in spite of you, not because of you.

ARA Is it pleasing to you when you’re invited to be part of art festivals?

AP It’s pleasing in some ways, because for all these years, it didn’t happen and now, maybe accidentally, or because things that are considered political or ‘progressive’ are now entering the artworld in small ways, it is. But most of the time, what I see in the artworld is not politics, but the perfume of politics. It’s a very displaced kind of politics, where you see just a little touch of it, but don’t get into the depth or detail.

ARA Yes, I was going to ask, do you think it’s any different from the Meet Market you were talking about earlier, with regard to documentary film festivals?

AP One thing that I never have understood is what the economy of the artworld is? We’re talking not just about the moving image, but paintings, sculpture or whatever things people collect. Who collects it? Where does the economy come from? Obviously, it comes from the very well-to-do. What if my work enters that space? I don’t say no to it, but it doesn’t make me call myself an artist. It’s just that I’m glad that some people think that there’s importance in what is being said and that importance is not just the politics of what is being said, but even the way that it’s being said.

I chose the documentary medium over a process of time, because I was interested in material I found in real life, and not in what I created myself. It’s not my creativity that I’m trying to draw attention to, it’s actually other people’s creativity and other people’s situations that I’m documenting, and juxtaposing so that people will think about it. A documentary film is like photography that talks, as opposed to photographs that might rob the images of the people in it without giving them voice. When people speak, you are allowing a process of communication to take place between different sections of society.

Every society is deeply stratified, and Indian society more so than most with the caste system and with the huge disparity between the rich and the poor. This act of just taking people’s voices from one section of society to another is not only a process of taking the voices of the dispossessed and showing them among the possessed, but also the other way around. We take the voices of people who have power and let people who don’t have power look at what they’re saying.

It’s a process of cross-fertilisation.

ARA But this can have its own problematics. As you said earlier, you yourself belong to an upper caste, and in the past you’ve been criticised, albeit by just one or two people, for making films about Dalits but not being a Dalit yourself.

AP Thankfully the criticism has never come from people in the Dalit or working-class neighbourhoods where I’ve done hundreds of screenings after the films were made, and where they were wonderfully received. Indeed, the fact that I am ‘upper caste’ by birth was either never noticed or was never seen as a bad thing in itself. People were empowered by the fact that they were on the big screen and that their voice now had the potential of reaching out to many. The criticism you mention has come from a few academics influenced by postmodernism for whom the very idea of class solidarity and the idea of building a rainbow alliance against injustice has been reduced to ‘What right does A or B have to say something unless they come from the exact same background?’ If that were the norm I would not be able to make films about patriarchy, about the homeless, about workers, about oppressed minorities or indeed about any injustice that I witnessed but did not experience personally. I would then be reduced to making films about my own navel.

I’m not saying that there is absolutely no merit to such an argument. It’s true that if the only voices that could be heard were voices from the upper caste, and upper class talking about injustice to the poor and the powerless, that would be a serious problem, but that is not the case. I don’t see this as a competition. I think that thousands of people from all sections of society must speak out about injustice, and it’s beginning to happen as technology becomes accessible. For me, all those who are actually fighting against injustice are on the same side, and may our tribe increase till we rise to a crescendo.

As someone born into privilege, I always felt a greater responsibility to speak up because privilege gave me some slight protection. A Dalit filmmaker might still get away because the present government is wooing the Dalit vote, but had a Muslim made In the Name of God/Ram Ke Naam [1992] or Reason it is unlikely he/she would be alive today. In fact, sections of the extreme-right Hindutva have killed even upper-caste Hindu opponents, as Reason highlighted. In 1948 Gandhi too was murdered by the Hindu upper-caste rightwing, so the protection provided by one’s birth caste, while it exists, is not exactly bulletproof.

I think that those who don’t see my films as acts of solidarity with the struggles that are taking place but choose to reduce them to acts of appropriation aren’t actually watching the films. They’re just watching me, and that too from a distance.

If there were a critique of the film itself, I would take it seriously, but that has not happened, except from the rightwing, which of course attacks my films incessantly as ‘anti-Hindu’ or ‘anti-national’. I would appreciate and learn from any critique made by nonrightists who actually looked at how my films were made or what the films were saying. It’s just that, at this point in academic history, identity politics has become fashionable and allows some people to become mentally lazy and attribute everything to birth. But it is a double-edged weapon. Identity politics is most useful when oppressed people need to assert their identity to come together, but the moment it goes beyond that and every- thing is reduced to identity, then you lose out on the opportunity to build alliances. You lose out on the opportunity to build a viable movement that can annihilate caste or overthrow other systems of injustice. In fact, you end up perpetuating the injustice that is going on because you subdivide all resistance by caste, class and gender.

ARA I presume that the worst thing that could happen to you is if everyone liked one of your films and agreed with everything in it.

AP Yes, the worst thing that can happen is all praise, or all criticism, and no discussion.