Filmmaker as Activist

The Hindu, May 16, 2004

ANAND PATWARDHAN’S films have always been in the thick of controversy. It’s not difficult to see why. His films are a mirror that society would rather not look into because of the disturbing images that they reflect.

Political, social and developmental issues have been central to his films beginning with “Waves of Revolution” in 1974. This was Jayaprakash Narayan’s anti-corruption movement in Bihar. From there he moved on to a critique of the Emergency (“Prisoners of Conscience”, 1978).

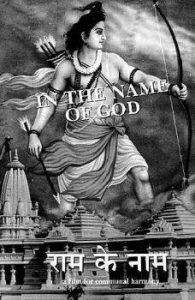

His other films focussed on the slumdwellers of Mumbai (“Bombay Our City”, 1985); the controversy over the Babri Masjid (“In the Name of God”, 1992); the link between communal violence and a patriarchal society with a close look at the metaphors of male virility (Father, Son and Holy War, 1994); the movement against the Sardar Sarovar dam (“Narmada Diary”; 1995); a devastating indictment of the nuclear bomb (“War and Peace, 2002).

Given the critical nature of his films, it has taken protracted legal battles before they are telecast on the national network Doordarshan.

In Chennai recently, for a screening of his film for the Youth Initiative for Peace, Anand Patwardhan, in an interview with R. KRITHIKA, spoke about of his films and the controversies they generate.

WHY did you choose filmmaking as your medium of expression?

WHY did you choose filmmaking as your medium of expression?

IT began more or less by accident. I was on a scholarship, studying sociology in the U.S., during the Vietnam War. My university was very active in the anti-war movement and I ended up going to jail twice for non-violent protests. I also borrowed a camera from the Film Department and shot some of the demonstrations.

I returned to India in 1972 and worked in a rural development project. Here, among other things, I made a short filmstrip about tuberculosis for our rural clinic. Later, in 1974, I joined the anti-corruption movement in Bihar led by Jayaprakash Narayan.

One day, when we anticipated police repression at a large rally in Patna, I borrowed Super 8 cameras and a friend, Rajiv Jain, and I shot the events of that day. This footage was then blown up to 16 mm, using the crude method of re-filming it off a screen. Afterwards another friend, Pradip Krishen, came to Bihar with his second-hand 16 mm camer. From all this material the film “Waves of Revolution” was born. Within months, the Emergency was declared. Many activists we had filmed were put behind bars and the film itself went underground till the Emergency was lifted in 1977.That was the beginning.

Filmmaking was born out of activism and, although this link is more tenuous today, filmmaking and film screenings remain, for me, a means of intervention.

Considering that your films are all issue-based, how do you find the funds ?

I decided long ago that I would not apply for large grants, foreign or Indian, and would keep my political and artistic independence by maintaining financial independence as well. Initially, the films were made with small donations in cash and kind from friends and relatives. Later I was able to sell my films and survive as long as I continued to make low budget films. Over time, I also bought my own film equipment and this further enabled me to keep costs down. It took a while but now I am able to recycle the profits from older films into the budgets for newer ones.

You have had problems with the authorities; how do you ensure that your films reach the audience?

You have had problems with the authorities; how do you ensure that your films reach the audience?

The connection with activism helps. Movements that I’m associated with during the filming are natural users of the films. The films also reach beyond these circles through film societies and film festivals in India and abroad and get further circulated. I believe, however, that most of these films are grossly under-utilised. They are unable to make a dent in the political reality for the simple reason that the vast masses of our society do not have access to them. So I have always fought hard to screen my films on the national network of Doordarshan (DD). Whenever my films won national awards, I submitted them for telecast. When DD rejected them, I successfully fought court cases to force them to screen my work. So far three films were telecast after court orders. We recently won a new case and DD will soon have to telecast my 1995 film “Father, Son and Holy War”.

Parts of “War and Peace” were filmed in Pakistan in the aftermath of Pokhran 1998. Were there tense moments?

If you see “War and Peace”, you will know that, contrary to expectations, peace activists from India received tremendous love and friendship from the ordinary people of Pakistan. Of course, there were the odd fundamentalist types here and there but from what I could see there is less of a “Hate India” prejudice in Pakistan than vice versa. Fundamentalists in Pakistan have never been widely popular. They have never won more than a few seats in Parliament. Here we elected ours to power.

How do you find the many unknown, ordinary people in your films who make such a powerful impact on the viewer?

One problem with our democracy is that a rigid class and caste hierarchy coupled with gross gender inequality has kept large sections of our population traditionally without a voice. But having no voice does not mean having no brain! On the contrary the voiceless have much to say and we can learn so much from their ways of seeing and thinking. Feelings of humanity seem to survive much better amongst the powerless than among the affluent and powerful.

Whether in the tenements of Mumbai or in the villages around Ayodhya, I found Hindus and Muslims who lived and ate together and swore by each other even in times of crisis. Similarly, in the midst of mass hysteria and blind faith in Sati in Rajasthan, I came across a working class woman whose wisdom and reason remained steadfastly intact. In Mumbai after the riots of 1992-93, I met a woman who had been raped. Her husband was killed virtually in front of her eyes and yet her humanity remained alive. In Hiroshima I met an old man who had lost his parents in the atomic explosion. He had become a Buddhist. He said to me “Hatred cannot overcome hatred”. How do I find such people? They are everywhere. All you have to do is keep your eyes and ears and your heart open.

Two years ago a scheduled screening of your films at the American Museum for Natural History, New York, was indefinitely postponed due to pressure from militant Hindu activists. What were your reactions?

It was a shameful chapter. “In the Name of God” which won a national award in India and was screened on Doordarshan after a court order, was not shown in the American Museum because some Hindu fundamentalists objected. Why the post 9/11 U.S., while ranting and raving about its “War on Terror”, gave in to threats by fundamentalists is an interesting question.

Why did you include the United States in “War and Peace”?

To talk of the stupidity, venality and criminality of those who advocate the Indian and Pakistani Nuclear Bomb without including a critique of the only nation in the world that has used the Atom Bomb would have been a travesty. Beyond this is the fact that Third World elites — the politicians, the scientists, the defence analysts and their business partners — aspire to the same jingoistic bombast they see emanating from Big Brother U.S. Once again it is to the ordinary citizens we must turn for our moments of hope.

What do you make of the attitude that those who oppose the bomb are “traitors”?

How patriotic is it to love your land so much that you are willing to make it radio-active for millions of years? The truth is that the antecedents of those who trumpet their patriotism today are people who supported British rule. An exception was V. Savarkar but even he got his sentence in Andamans Prison shortened on the plea that he would never fight the British again. He stuck to this bargain and concentrated on fighting Islam instead. His final contribution was instigating the murder of Mahatma Gandhi. If this is patriotism, I want none of it.